Timeline

500 Years Ago

1526

In November 1526, the first reference to the Deputy Treasurer named Master Chydley appears in the Inn’s records.

“Peter Faunt le Roy pardoned all penances for 26s. 8d., whereof he paid to Master Chydley.”

– Parliament 16 November, 18 Henry VIII A.D. 1526

Since its inception, the Inn has had a Treasurer annually elected from amongst the Benchers. Their duties were to admit to the Society such as they thought fit, assign chambers to members of the Inn, collect pensions or dues and to receive the fines on admissions to chambers; to pay all wages and appoint all subordinate officials and to render an annual account of their office, which was audited by members of the Inn, and to maintain the Inn.

The Treasurer’s tasks became more extensive as the Inn’s membership grew, making it necessary to employ the assistance of another member of the Inn in the role of an unofficial Deputy Treasurer, who was chiefly responsible for the collection of debts.

In 1682, this was made a permanent position with the appointment of Anthony Belbin as Sub-Treasurer, who undertook many of the tasks previously performed by the Treasurer.

400 Years Ago

1625–6

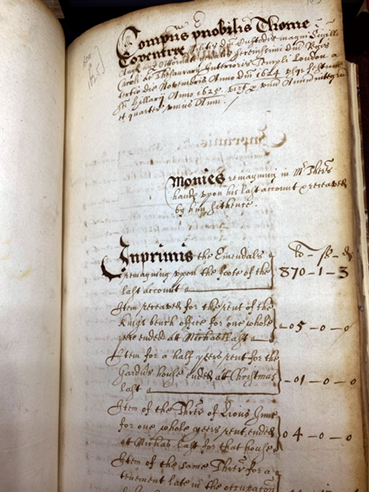

Account of Thomas Coventry, Treasurer from 3 November 1624 to the Feast of Hilary 1625–6, being one year and a quarter.

The account of the Treasurer provides considerable insight of the goings on at the Inn. It is notable that the largest payments were for the Inn’s wine.

Payments by the Chief Butler:

- For a play on Candlemas Day 1624, 7li.

- For the musicians that day, 1 li.

- To watchmen for watching the House at Christmas vacation, 1li. 17s. 6d.

- Given to the gentlemen revellers three times in Michaelmas and Hilary terms, 3li.

- For torches for the revels, 15s.

- For leather laces for the church Bible, 2d.

- For faggots for a bonfire when the Queen landed, 5s.

- Given to my Lord Chief Baron and Baron Trevor when they were made Serjeants, 10li.

- For two purses to put the money in, 2s. For a warrant to apprehend Ramsey’s sons for suspicion of breaking open Serjeant Owen’s Chamber, 6s. 4d.

- To the Master of the Temple for his stipend, due to him at Lady Day, 1625 from this House, 4li. 6s. 8d.

- To the vintner for the wine, 31li. 8s.

- For sack and muscadine, 13s. 6d.

- For laying in wine this year, 12s. 10d.

300 Years Ago

1725–6 The Temple Foundlings

The Inns of Court were forced into the role of social welfare for abandoned infants, with large numbers of children abandoned on their doorsteps. This practice had become a regular feature by 1661. In the course of a year, usually three to four children would be ‘dropt’.

At the time, legal responsibility for the poor and destitute fell upon the parish. An illegitimate child was settled in the place it was born. The Inns were extra parochial and so were not part of any parish and were not liable to pay the poor law rate levied by any of the surrounding parishes, resulting in them been left literally holding the baby.

Middle Temple has a book listing these children, entitled Exposed Children, with details of their short lives and the payments required to keep them. The Inner Temple accounts contain numerous references to these children whom it arranged to be baptised and wet nursed by local women and occasionally by servants of the Inn.

The few children who survived the multiple childhood illnesses prevalent at the time were apprenticed to local tradesmen, such as shoemakers or embroiderers. All the children were given the surname ‘Temple’.

In 1725, a girl baby was abandoned in Fig Tree Court (now part of the Eastern end of Elm Court) the ownership of the precise piece of land on which she was found was put on the agenda for a meeting with the Middle Temple. The responsibility was given to the Middle Temple, although sadly she died three weeks later.

The last recorded abandonment was in 1845.

200 Years Ago

1826

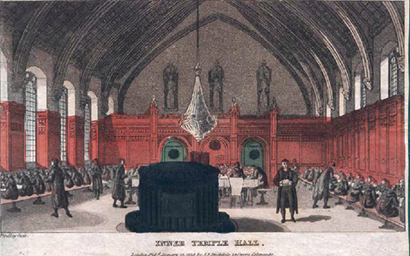

Dinner in the old Hall mezzotint by Finlay, 1826.

This mezzotint shows the Inn’s medieval Hall before it was replaced in the late 1860s. It is thought to be built on the site of the old Knights Templar Hall, perhaps incorporating much of the old building within it.

It has been described as homely rather than magnificent, with buttressed walls, gothic windows and a louvre on the roof to take smoke from the central hearth, which served as the only fireplace. In 1632, the Hall was described as “ruinous and decayed”. Until its replacement in 1867–70 this was the oldest of the secular buildings in the Inns of Court.

The image also shows the large furnace used to heat the drafty building, in place of the former fireplace. The members are shown in gowns, dining in their messes (a group of four barristers).

A description of dining in Hall is provided by an Irish student in 1860, just before its destruction:

“Each mess has its dinner served to it separately – the meat on large pewter plates – and enjoys its own bottle of wine. Every mess has its ‘captain,’ an officer whose privilege it is to help himself first to everything and whose duty it is to preserve order amongst the members of his own mess. The meat is not carved by any one individual for the others, as it is at our more modern and more civilized King’s Inns in Dublin, but everyone helps himself.”

Jamie Briggs

100 Years Ago

1926

The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 2019 opened the legal professions to women and allowed them to become barristers. One such woman was Ma Pwa Hmee, the first Burmese woman barrister.

Ma Pwa Hmee was admitted to this Inn on 25th January 1924. As a strong supporter of women’s rights, she initially decided to become a lawyer in order to benefit the women of Burma, believing that:

“Many Burmese girls were well educated but were too timid to take up public work and needed encouragement.”

One of her letters of testimonial for entry to this Inn was written by the former Lieutenant Governor of Burma, Harvey Adamson, who stated that:

“Her family is well known and respected in Burma. Her father holds a position of trust in Rangoon Municipality. Ma Pwa Hmee has come to England to study for the Bar, an enterprise which I believe no other Burmese lady has hitherto undertaken. From what I see and hear I am confident she is worthy of encouragement”.

As a strong supporter of women’s rights, she initially decided to become a lawyer in order to benefit the women of Burma, believing that: “Many Burmese girls were well educated but were too timid to take up public work and needed encouragement.”

Ma Pwa Hmee was called to the Bar on 17th November 1926. As only one of two women to be called to the Bar, she attracted the attention of the press and was interviewed, providing us with a description on London and Londoners through the eyes of a Burmese student in London:

“Never in my life had I seen people in such a hurry as those tearing down the streets of London. I thought that their haste must be due to some special attraction in the next street. In one of the busy streets of the West End I remember waiting five or ten minutes to cross the road and expecting the traffic to wait for me. Another of my difficulties was in understanding the language of the bus conductor who several times told me to ‘Ole tight’.”

She also mentioned the dress of the British girl:

“They have none of the daintiness of our national costume, but of course our dress would be ridiculous here, for we wear skirts down to our ankles and we could not possibly run to catch the buses and trains as British girls do.” She admired “the bearing of the British people, their erect bodies and even strides which show they have loved for generations long walks in the open air.”

On 10th December, she boarded the boat back home and in 1927, she became the first woman to be called to the Bar in Rangoon.

Celia Pilkington

Archivist