ICLR

If it's reportable, we report it.

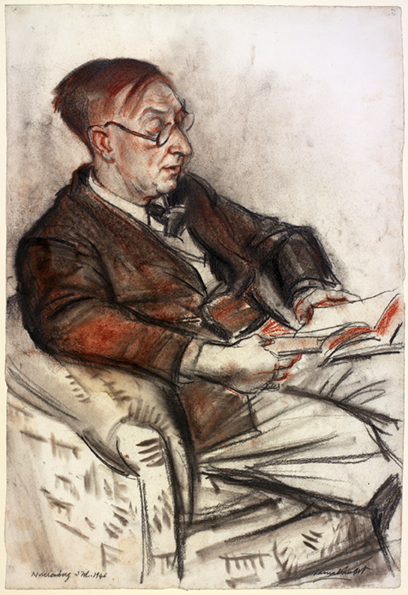

Geoffrey Dorling Roberts, 1946 © IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 5862)

“The Trial which is now about to begin is unique in the history of the jurisprudence of the world and it is of supreme importance to millions of people all over the globe… [It] is a public Trial in the fullest sense.”

These words by Sir Geoffrey Lawrence, later Lord Oaksey, opened his first speech as the President of the International Military Tribunal (IMT) in Nuremberg. The magnitude of Lawrence’s historic statement continues to resonate 80 years after the trials, in a world where the legacy of Nuremberg has shaped both international law and collective memories. Members of The Inner Temple – such as Lawrence, Treasurer in 1954 – played a key role in the trials and their legacy, cementing the Inn’s place as a major institution in the development of international justice and human rights law. Traces of this legacy can be found in the Archives and Library of The Inner Temple and are reflected in work still carried out today by members of the Inn.

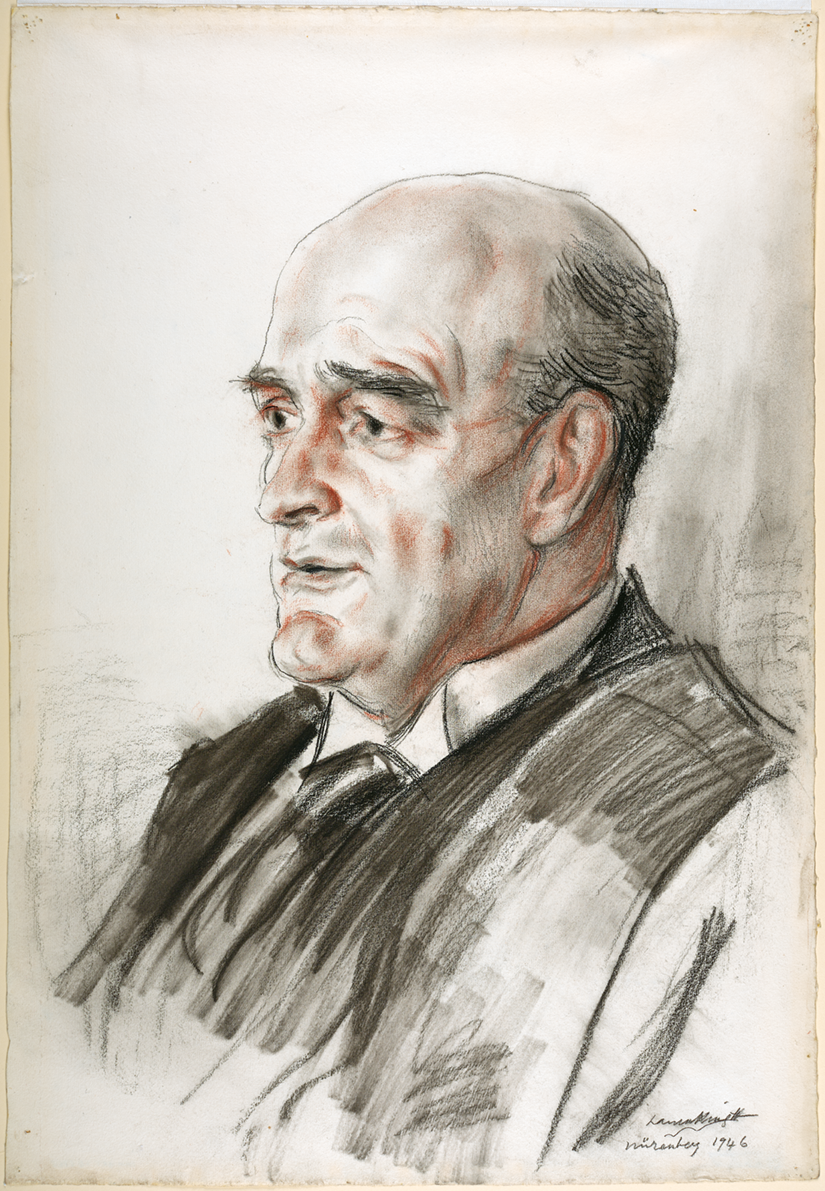

The Nuremberg Trials were held between November 1945 and October 1946, prosecuting senior members of Nazi leadership following the surrender of the regime in May 1945. The International Military Tribunal, composed of legal representatives from Britain, France, the Soviet Union and the United States, judged 22 defendants on counts including crimes against peace and crimes against humanity – novel legal frameworks born out of the unprecedented horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust. Several members of The Inner Temple were actively involved in the application of these new charges within the British prosecution team at Nuremberg – among them Sir Geoffrey Lawrence (called 1906), British President of the International Military Tribunal (IMT); Sir Norman Birkett (called 1913), seconding Lawrence as alternate judge; Geoffrey Dorling ‘Khaki’ Roberts (called 1912), leading counsel; and Anthony Marreco (called 1941), junior counsel. Many of these men kept diaries and wrote memoirs about their time in Nuremberg, several of which have been kept at the Inn, preserving first-hand experiences of the trials.

ICLR

If it's reportable, we report it.

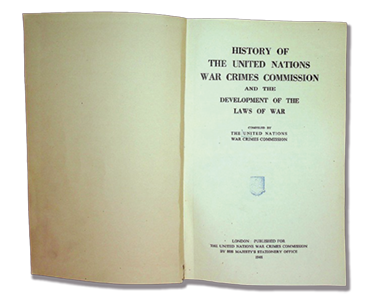

Trusted law reporting since 1865

Before the commencement of the trials, however, other members of the Inn were involved in the long negotiations regarding the planning of the post-war prosecution of German war criminals. From October 1942, John Simon, 1st Viscount Simon (called 1899), proposed to the House of Lords the creation of an Allied commission for the investigation of Nazi war crimes to “collect material, supported wherever possible by depositions or by other documents, to establish such crimes […] and to name and identify those responsible for their perpetration”. Another member of the Inn, Lord Wright of Durley (called 1900, Treasurer 1946), chaired this commission on its creation in 1943 as the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC). The commission collected evidence against the Nazi regime as Allied armies progressed through Europe, providing the bulk of the evidence used in the post-war prosecution process. In Lord Wright’s words in his History of the United Nations War Crimes Commission, the UNWCC would “investigate and record the evidence of war crimes, identifying where possible the individuals responsible”, directly referencing Simon’s demands of 1942.

With the formal German surrender in May 1945, the four-nation UNWCC met in London between 31 May and 2 June 1945 to agree the next steps. In his opening speech, Lord Wright of Durley emphasised the need to move towards “the punishment of the criminals for the double purpose of retribution to satisfy the people’s demand for justice, and of warning and example to deter such crimes in the future”, already highlighting the role of Nuremberg as a template for a new model of international criminal law. Ratified on 8 August 1945 as the London Agreement, with an annexed charter creating the IMT and outlining new charges presented at the Nuremberg Trials, the agreement became a landmark moment in the development of international jurisdiction on war crimes. Building on the recommendations first articulated by John Simon to the House of Lords in 1942, Lord Wright’s actions as chair of the UNWCC would cement the ties between The Inner Temple and Nuremberg – ties that continued through the active participation of its members at the trials.

With the opening of the trials in November 1945, four members of The Inner Temple were present in the courtroom of the Justizpalast. Several files have survived which recount their role in the indictment of Nazi war criminals. In his memoir, Without My Wig, Geoffrey Dorling Roberts recounts his first impression of the German leaders in the dock: “There was Göring, not jovial, with the ghost of a smile on his lips; Hess, reading a book, taking no interest in the proceedings; and Ribbentrop with his nose in the air, […] obviously strongly disapproving of the whole thing.” Anthony Marreco also noticed these attitudes in an interview given in 1998, where he described Göring as the “star of the show”, a disgraced leader with his “white field marshal’s uniform [which] was hanging like a toga loosely on him”, oscillating between good form and “tremendous depression”. Marreco would play a key part in the case against Admiral Karl Dönitz for his role in the unrestricted submarine warfare against merchant ships in the Atlantic. This case saw the application of the new charges of crimes against peace and crimes against humanity, ultimately only costing Dönitz a ten-year sentence.

For Marreco, the sentences carried out at Nuremberg were lenient considering the gravity of the crimes. Following the testimony of a French Auschwitz survivor, Marie Claude Vaillant-Couturier, Sir Norman Birkett described with revulsion what he saw as the “most terrible and convincing case of complete horror and inhumanity in the concentration camps”. Geoffrey Dorling Roberts similarly recounted the projection of the American documentary Nazi Concentration Camps in the courtroom: “A normal vocabulary is unequal to describe the horrors of this historic record: reel after reel of corpses, exhumations, gas chambers, body disposal plants, instruments of torture; men and women, all skeletons, some just alive.” The exposition of such crimes to the public, thanks to the extensive mediatisation of the trials, is another central aspect of Nuremberg’s impact on collective memory. These images would shape public awareness in the extent and barbarity of Nazi crimes and lead to a series of Holocaust trials in the decades following Nuremberg.

The British duo of judges at Nuremberg, Sir Geoffrey Lawrence and his second, Sir Norman Birkett, sat for the 11 months of the trials. Their involvement in every step of the proceedings and gained them the admiration of colleagues. For the American alternate judge John J Parker, “no one connected with the Tribunal, member or otherwise, had a greater part than Birkett in shaping the final result”, with Birkett hand-drafting a large part of the judgment and whose opinion was heard in every deliberation. Despite Lawrence’s commanding and respected authority over the trial as President, some noted the major influence of Birkett, who assembled the bulk of the British delegation’s case against German leaders. This exacerbated pre-existing tensions between both men, with Birkett snubbed for the role of leading judge in favour of Lawrence, an experienced judge from the Court of Appeal. Marreco praised the performance of both men, noting that Lawrence “had the respect of the whole bench”, yet saw that Birkett, under strenuous pressure and disappointed with his appointment as alternate judge, “was never very happy at Nuremberg”. Despite such disagreements, the trials ran smoothly with the final verdict given on 1 October 1946 by Sir Geoffrey Lawrence: 12 defendants were sentenced to death, seven to imprisonment and three acquitted.

The involvement of The Inner Temple members in these historic trials, however, transcends the walls of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice. Two members also played an active role in the resistance against the very crimes discussed at the trials, a further notable connection between the Inn and the fight against Nazi violence. Within the German administration, Helmuth James von Moltke (called 1938) pursued undercover resistance to the regime as an agent within the Abwehr foreign intelligence service. With access to clear reports about atrocities committed by German forces in occupied territories, Moltke leaked plans for the deportations of Danish Jews, allowing for the majority to find safety in Sweden, and planned two visits with British contacts in Turkey to transfer confidential information to the intelligence services, some of which found its way as evidence in the Nuremberg courtroom. His organisation of secret anti-Nazi meetings at his family home in Kreisau would involve him with other activists envisioning Germany’s future after the fall of the Reich, with Moltke himself advocating for a special international criminal tribunal to be convened after the conflict to judge war criminals. The ‘Kreisau Circle’ and much of the Abwehr leadership would, however, be purged by the Gestapo in 1944, with Moltke found guilty of treason and executed on 23 January 1945 in Berlin. A book collecting Moltke’s moving letters to his wife, Freya, is held at the Inn’s library, underscoring his humanist values; writing in 1940, Moltke affirmed that “whoever knows at all times the difference between good and evil, and does not doubt it, however great the triumph of evil seems to be, has laid the first stone for the overcoming of evil”.

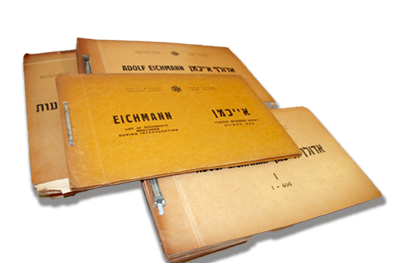

Members of The Inner Temple thus played a fundamental role in exposing war crimes committed during the conflict as prosecutors, informants and dissidents. After the war, members were actively involved in the perpetuation of Nuremberg’s – and Moltke and Karadja’s – visions of international justice and fight for human rights. Junior counsel Anthony Marreco later became a founding director of Amnesty International alongside Peter Benenson in 1961 – an organisation created in The Inner Temple’s Mitre Court, defending the human rights of prisoners across the world. The same year, Lord Russell of Liverpool (admitted 1928), who had served as legal adviser in later trials of German criminals in the 1950s, attended the Adolf Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, bringing back a collection of original evidence that was kept in The Inner Temple archives until 2008. Such an enterprise directly echoed Sir Norman Birkett’s wish for trials “secure against all criticism, […] convincing and built on evidence that cannot be shaken as the years go past”, and for the precise documentation of the horror and extent of crimes against humanity for future generations (Norman Birkett: The Life of Lord Birkett of Ulverston (1964), H Montgomery Hyde).

Elsewhere in occupied Europe, Prince Constantin Karadja (called 1922) would play a paramount role in the saving of 51,000 Romanian Jews from deportation to extermination camps by German forces and the collaborationist regime. Through his role as a senior member of the Foreign Ministry, Karadja signed off the repatriation of Romanian Jews from Hungary, Germany and France to their homeland, supplying them with travel documents and convincing colleagues at the ministry that this relocation would be temporary until emigration to Palestine. Karadja had seen first-hand the extent of Nazi violence towards Jews as Consul General in Berlin between 1931 and 1941, writing reports to his government about the Kristallnacht in November 1938 and the growing climate of antisemitic hostility driven by Nazi rhetoric. Karadja continued to follow his clear sense of justice and humanity after the commencement of hostilities, supported by his training as a lawyer. In a 1943 letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, he denounced the open violation of rights exercised by German troops, stating that “in international law, the principles of universal ethics and the fundamental rights of mankind are not taken into account by the German authorities” and that “every minority, like the Jews, has to submit not only to the laws of the country, but also has the right to diplomatic and consular protection”. For his brave actions, Karadja would be posthumously awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations in 2005.

The trials were finally a watershed moment in the development of the international prosecution of war crimes, as the first instance of violators of international law being charged for their actions. The Nuremberg Principles were enshrined by the United Nations International Law Commission in 1947 to define the scope of war crimes and were followed a year later by the United Nation’s Convention of Human Rights, which asserted the rights and liberties of citizens on a global scale. Despite the strong initiatives taken in the years following the Second World War, the 20th century bore witness to new genocides in clear violation of international law in Rwanda and Yugoslavia. Born out of the ashes of the International Criminal Tribunals for both genocides, the permanent International Criminal Court’s creation in 1998 was a clear continuation of Nuremberg’s goals. Today’s members of the Inn have built upon the work undertaken by Inner Templars at Nuremberg and beyond for the protection of human rights and prosecution of perpetrators, serving in institutions such as the International Criminal Court, the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, perpetuating the clear commitment of the Inn to the defence of human rights.

Hector Le Luel

Archives Volunteer