The Bubbly Show 2026

6-7 March 2026

Sip on the world’s finest Champagne and English Sparkling Wine

Unlimited tastings | curated lunches | indulgent dinners | elegant afternoon teas | expert-led masterclasses

“London’s favourite Champagne Festival”

From a Reader’s Lecture held on 13 November 2024

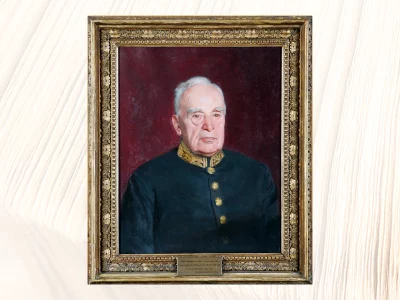

Lord Wright GCMG, Treasurer 1946, Lord of Appeal in Ordinary 1932–1935 and 1937–1947, Master of the Rolls 1935–1937., by Sir Gerald Kelly PRA 1952

© The Inner Temple Collection

Let me begin with some history, building to an extent on my book Making Commercial Law Through Practice 1830–1970 (2021). I’ll then say a little about people, and finally move on to what I call, rather misleadingly, practical judging, drawing to an extent on my current book, Judging (forthcoming, 2025). I’ll do this by using as a staging post for some thoughts about these huge topics a member of this Inn, one of the England’s great commercial judges, and also one who had an academic bent.

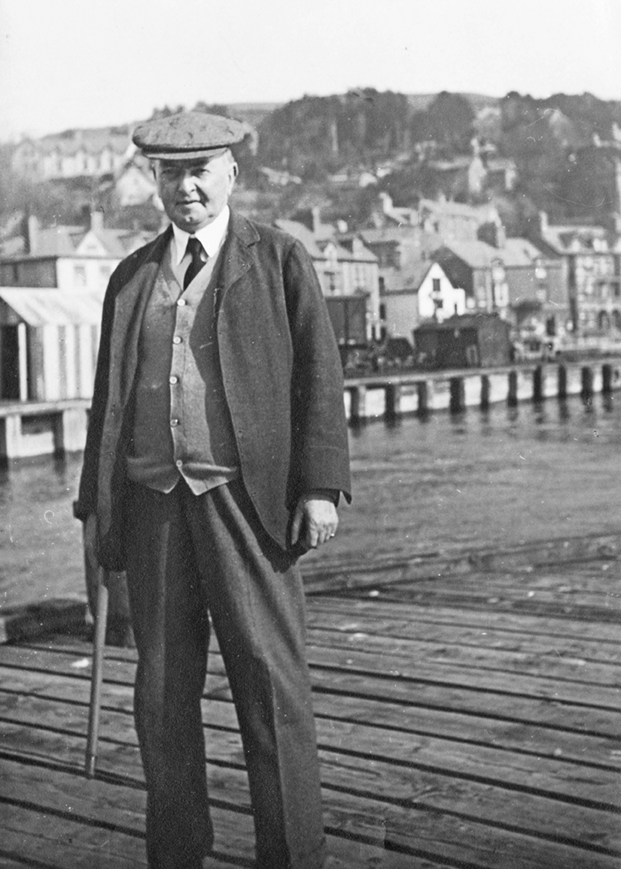

Robert Alderson Wright did not have early success at the Bar. He lectured for over a decade in the evenings at the London School of Economics (LSE) in Industrial and Commercial Law. His teaching is recalled in the dedication to Holdsworth’s 12th volume of A History of English Law. Indeed, at one point Wright considered becoming an academic lawyer. But he stuck with the Bar and his practice eventually took off during World War I when others went into the services – he was too old. He was appointed to the High Court in 1925, going straight to the House of Lords in 1932.

Unlimited tastings | curated lunches | indulgent dinners

| elegant afternoon teas | expert-led masterclasses

“London’s favourite Champagne Festival”

The Bubbly Show 2026

6-7 March 2026

Sip on the world’s finest Champagne and English Sparkling Wine

My colleague at the LSE, Professor Neil Duxbury, characterises Wright as a “innovative traditionalist”. Wright was effective as a judge in subtly developing the law, without undermining established precedent and statutory authority. He describes how Wright applied his belief that development of the law is necessary because rules sometimes produce absurd and irrational consequences if rigidly applied. In his speech in Northumbrian Shipping Co. v Timm [1939] AC 397, Wright said: “Commercial law has always been ready, so far as possible, to sacrifice pedantic logical consistency in favour of the convenience in the conduct of business.”

So that’s my first point: as a matter of what I would call legal policy, historically, English judges have sought to accommodate the law to commercial life. They have done this in various ways. The first was the employment of commercial custom, used in two ways, to interpret contracts and to supplement their language by implying terms. There is a volume of cases where judges recognised the custom of ports, trades, and markets, but it was also used at the beginning of asset finance and in 1875 in high finance in the famous case of Goodwin v Robarts (1875) L R 10 Exch 337 to extend negotiability to the international bonds. In a 1940 case involving the sale of American wheat Lord Wright held (the other Law Lords agreeing) that the arbitrators could cure the ambiguity in a clause in a standard form commodity contract “by importing the custom and practice of the trade”: (1940) 67 L l L Rep 147. By the 1950s, however, as Lord Devlin put it in a lecture at the LSE, custom “can no longer be regarded as a revivifying source of commercial law”.

Secondly, English judges played a facilitative role historically in areas of doctrinal law. An example is sales, at one time the very centre of commercial law. In the early 19th century judges recognised that there needed to be implied terms in a contract of sale – terms which became a cardinal feature of our law, and also our language – goods had to be fit for purpose and merchantable, the latter graphically expressed in Lord Ellenborough’s famous dictum: “The purchaser cannot be supposed to buy goods to lay them on a dunghill”. Judges held that sale had a wide reach as with Lord Wright’s decision in 1934 in Cammell Laird and Co Ltd v Manganese Bronze and Brass [1934] AC 402. The terms were codified at the end of the century by Mackenzie Chalmers in the Sale of Goods Act 1893.

Unlimited tastings | curated lunches | indulgent dinners

| elegant afternoon teas | expert-led masterclasses

“London’s favourite Champagne Festival”

The Bubbly Show 2026

6-7 March 2026

Sip on the world’s finest Champagne and English Sparkling Wine

In codifying these and the other rules in what became the Sale of Goods Act 1893, Chalmers’ stated aim was to further “certainty and definitiveness” and to facilitate commerce. But the key point is this: Chalmers saw his codification as containing default rules, which only applied when the parties had not formed an intention or failed to express it. And this freedom to contract out of statutory and doctrinal law regimes is the third, and a vital feature of English commercial law. As a result of party autonomy, historically commercial parties have been able to engage in private law-making.

So there were standard form contracts for markets, shipping, and insurance; institutional rules for places like the Baltic Exchange, the home for chartering and buying and selling ships and until the mid-20th century international grain trading; the London Clearing House, which provided and still provides clearing services for international trades, these days in commodities, swaps, derivatives, foreign exchange products, etc, and other financial institutions such as the London Clearing House for payments. Party autonomy is precisely what happened in practice with sales, as with international commodity sales where quality standards and remedies implied by law were excluded and laid down instead by the various trade associations in their standard form contracts.

The other side of the coin to freedom of contract – the fourth feature of English commercial law – stood sanctity of contract, as Wright put it on one occasion, only to be overridden by the strongest possible counterbalancing circumstances. Bright line rules – legal certainty – enabled parties to plan their transactions. It did mean that just because a turn of events bore heavily on parties to a commercial arrangement, or circumstances significantly changed to their detriment, that was no justification for curial intervention. But in a more general sense freedom of contract came to the rescue. If parties to a standard form contract or in a particular market were caught out by a situation or a judicial ruling, there was the legal possibility of rewriting the contract, although given the power configurations in a market commercially this might not be feasible.

None of this means that the English judges were always supportive of commercial practices or in the vanguard in making new law. When they were it was often after a commercial practice had been developed by merchants, or an innovative legal technique had been contrived by the profession, and these had become entrenched. What the judges did – and we shouldn’t underestimate its value – was to give their imprimatur to those practices and techniques. Hire purchase, now asset finance, offers just one example of the courts approving a well-established commercial practice, when the hire purchase trade took the test case of Helby v Matthews [1895] AC 471. Other examples are bank overdrafts (the main avenue for trade credit) and letters of credit. With documentary credits, as with the work of confirming agents, the courts brushed aside what might have been a doctrinal roadblock, the lack of consideration, to endorse a well-established commercial practice. And with the Gaming Acts, legislation was read down, so as not to disrupt dealings on futures markets. In Professor Sir Roy Goode’s colourful phrase, there was the power of a market “to pull itself up by its own legal bootstraps.”

Let me turn to my second topic, people, specifically, to some of the leading commercial judges who set the tone – although in focusing on the judges one should not underestimate the importance of the legal profession in forging English commercial law. For present purposes, the key point is the role of specialist judges in the success of English commercial law, not generalist judges, and certainly not career judges in the civil law tradition, judges who worked their way up in a state civil service tradition.

Lord Wright is an example. Little is known of his background, schooling, and early adulthood, but his father was a marine superintendent on Tyneside, and the late Dr Robert Stevens opined that it is almost certain that Wright absorbed a good sense of commercial practice from his father and in his early years of work, possibly was employed with him. This connection to commerce features with other judges making notable contributions to commercial law as well. Lord Blackburn’s father was a Glasgow merchant, who owned sugar plantations. Of course that meant he had enslaved people, in Jamaica, and as a corollary received substantial compensation after emancipation. Following his well-known book, Treatise on the effect of the Contract Sale (1845), Blackburn appeared as a junior in heavy mercantile cases. George Bramwell’s father was a banker and Bramwell served an apprenticeship as a clerk in the bank. Once the Commercial Court was established a considerable number of its judges had commerce in their family, Pickford was from the famous family of carriers, Walton, from a prosperous family of Liverpool merchants. There were merchants on Adair Roche’s mother’s side, and Frank Mackinnon was the son of a Lloyd’s underwriter, his mother the daughter of a timber broker, and his brother the chair of Lloyd’s on a number of occasions. Alan Mocatta’s family were bullion brokers.

And there are others as well, including of course Lord Justice Scrutton, a big figure in commercial law with his family history in shipping, shipbroking, insurance broking, marine salvage surveying, and later stevedoring. As with some others, Scrutton was an author on the subject, with books on mercantile law, The Merchant Shipping Act, and, still with us, in its 25th edition his Charter Parties and Bills of Lading. Scrutton appeared regularly in commercial cases against another of the great, albeit controversial figures here at The Inner Temple, J A Hamilton, Lord Sumner, the son of a Manchester iron merchant, the “Last Political Law Lord” as one biographer describes him.

Even without vicarious knowledge of commerce through family background, English commercial judges learnt their trade in commercial chambers. Lord Wright for example was, along with Richard Atkin and Mackinnon, a pupil of Scrutton with his enormous practice in shipping and insurance, as well as banking and sales. Later they too acquired large commercial practices and pupils, and so it continues to this day. So English commercial litigation, certainly after the foundation of the Commercial Court, was heard by judges and argued by counsel familiar with the ethos of commerce and its practices, in addition to their knowledge of substantive commercial law and procedure. No doubt they have brought that knowledge and sentiment to bear in their judging.

In the case law there are examples of other judges adopting commercial practice as a template for reasoning, albeit that it fell short of commercial practice.

That leads to my third theme, that judging involves more than legal knowledge and skills. One aspect is what the American jurist, and the main author of the US Uniform Commercial Code, Professor Karl Llewellyn called ‘situation sense’ which David Foxton draws on in his outstanding biography of Scrutton. It’s a feeling for what is the practical solution when faced with the circumstances of a case. Scrutton’s situation sense was not lightly worn and frequently expressed to justify his conclusions. So he paraded his knowledge of the China trade, timber dealings, the cold storage business, and so on in his reasoning. That did not mean that Scrutton always approved commercial practice. There are several decisions where he refused to endorse it. In the case law there are examples of other judges adopting commercial practice as a template for reasoning, albeit that it fell short of commercial custom.

The notion of ‘situation sense’ cannot be pressed too far. One reason is that even outstanding commercial judges cannot know every conceivable part of the commercial world. These days, in particular, specialisation sets in fairly early in practice. But intuition does play a role in judicial decision making. Lord Sumption, another member of this Inn, told Alan Paterson – the close student of Law Lords and Supreme Court justices for over five decades – that he had instinctive feelings, although their strength turned on the subject matter: “How often I am persuaded my initial instinct is just wrong in principle, well probably not very often. When it happens it tends to be in cases in subject areas which I am not so familiar with as some of my colleagues”: (Final Judgment, 2013).

Other than ‘situation sense’ and intuition, there is an enormous amount of US literature explaining judicial decision-making is a judge’s ‘attitudes’ and that their legal reasoning can be a rationalisation of these factors. One dimension is the judge’s notion of public policy. Another of this Inn’s great Commercial judges, Lord Goff, said on one occasion that the commercial judge’s role was “to help businessmen, not to hinder them. We are there to give effect to their transactions, not to frustrate them: we are to oil the wheels of commerce, not to put a spanner in the works, or even grit in the oil.”

A few high-level conclusions. First, English Commercial Court and commercial judges have generally attempted to facilitate commercial transactions. Secondly, people matter, in particular, the expertise of those settling (and litigating) commercial disputes, both the judges and the commercial Bar working together. Thirdly, we need more than the conventional tools of legal reasoning to understand judging. Practical judging involves factors like ‘situation sense’, intuition, and the judge’s notions of public policy.

Sir Ross Cranston FBA

Professor of Law, London School of Economics

For the full video recording:

innertemple.org.uk/englishapproach