The Bubbly Show 2026

6-7 March 2026

Sip on the world’s finest Champagne and English Sparkling Wine

Unlimited tastings | curated lunches | indulgent dinners | elegant afternoon teas | expert-led masterclasses

“London’s favourite Champagne Festival”

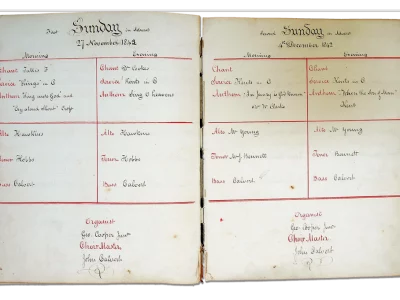

Inside pages of the choir book © Inner Temple Archives

The Temple Church Choir has an excellent reputation today, but history has forgotten that John Calvert was the founding choirmaster who established that reputation within his first year. In 1842, to mark the reopening of the Church after a long renovation, the societies of The Inner and Middle Temple hired Calvert to create a new choir to revive the treasures of English cathedral music by Renaissance and Baroque composers such as Thomas Tallis and Henry Purcell.

Deeply religious, Calvert felt this music gave listeners a foretaste of heaven. He built a star-studded choir that performed much rare music, attracting large congregations, royalty, and national press coverage. He resigned abruptly in 1844, undone by inexperience, idealism – and the duplicity of Inner Temple barrister William Burge.

This is the story of how Calvert founded the Temple choir, under the musical leadership of The Inner and Middle Temple. Calvert later roamed the Empire, leaving few papers. My main sources are the Inner Temple Archives’ rich collection and period publications. Unattributed quotations are Calvert’s words.

John Calvert (1816–1880) was a musical outsider. Most professional musicians had musical parents; Calvert’s were ivory turners, famed for exquisite chess sets. His widowed mother, Dorothy, educated three sons at Stockwell Park Grammar School. Two went to Cambridge. Christopher Alderson Calvert was at Middle Temple by 1838; William Calvert was an Anglican curate by 1843. John partnered his mother in D Calvert & Son until she died in 1840. Somehow, he trained in music and joined the cathedral musicians then beginning to revive early English music.

Unlimited tastings | curated lunches | indulgent dinners

| elegant afternoon teas | expert-led masterclasses

“London’s favourite Champagne Festival”

The Bubbly Show 2026

6-7 March 2026

Sip on the world’s finest Champagne and English Sparkling Wine

In 1841, he sang a concert with George Cooper Junior, assistant organist at St Paul’s Cathedral choir, where Calvert occasionally sang as deputy. Cooper’s circle included singers Enoch Hawkins and John Hobbs, both of the Chapel Royal and Westminster Abbey, and organists John Goss of St Paul’s and James Turle of the Abbey. All were famous stars and leading antiquarians, keen to strengthen the nation’s devotional life by reviving the early cathedral music. All of them – and Calvert – belonged to the Musical Antiquarian Society, then republishing early music, hard though it was to find.

These men supported Calvert as Temple choirmaster. Cooper and Bishop Copleston (Dean of St Paul’s) provided testimonials. Goss and Turle played for two public rehearsals before the launch. Hawkins and Hobbs became Calvert’s core singers and worked overtime helping him train the choir and find the music. None needed another job. Hobbs had declined a richer offer, “in preference for the Temple Church, for several reasons”.

Unlimited tastings | curated lunches | indulgent dinners

| elegant afternoon teas | expert-led masterclasses

“London’s favourite Champagne Festival”

The Bubbly Show 2026

6-7 March 2026

Sip on the world’s finest Champagne and English Sparkling Wine

Why? I think they wanted the Temple to set a national example of a well-paid choir singing the masterpieces of English musical heritage. Perhaps they hoped that the inexperienced Calvert’s charm, energy and antiquarian zeal would suffice until they could teach him how to run a choir.

The cathedral stars could not leave their lifetime appointments to lead the Temple choir. They also could not improve the infamously poor quality of Britain’s cathedral and collegiate choirs, then unable to afford enough good singers, their choral endowments having been long diverted elsewhere. The Temple, a collegiate church run by barristers, not clergy, and with no choir or endowment, could start afresh.

Barrister William Burge shared their goals. He led the two societies to start a choir that he later wrote “could become an example for other choirs, of infinitely greater influence… on the general character of Church music than… any other choral establishment.”

Calvert risked everything to get the job. He needed a permanent double choir for the characteristic antiphonal effect of Baroque cathedral music. In July 1842, he agreed to prepare a temporary single choir for the November reopening. The Church Committee had no hiring authority, so if the societies said no when they returned in autumn, Calvert was out, unpaid.

Days before the reopening, the societies said yes to one Sunday; days after, to eight more. He thrilled them with a double choir at Christmas, and in February 1843, they made him Master of a permanent double choir, for £450 per year, plus organist and music, far more than their previous budget of £120. Calvert took only £32 as choirmaster, half the going rate; but ultimately persuaded the societies to spend over £340 on a choir room and oak choir stalls, 25 guineas on a rehearsal piano, and £198 on music.

Calvert risked everything to get the job. He needed a permanent double choir for the characteristic antiphonal effect of Baroque cathedral music.

Calvert sang bass with his star soloists, but until the societies made the double choir permanent, he struggled to attract enough singers – most wanted stable jobs. So, he had his brother William sing five services.

While training his new choristers, Calvert programmed simpler choruses. A year later, Master Lloyd dazzled in treble showpieces – and stayed with the choir for decades. Enoch Hawkins had never known boys so admirably prepared.

In a beautiful Choir Book, Calvert documented a mountain of music by 40 English composers performed in 112 services. Most was Baroque: 60 of 65 anthems, 11 of 16 services, and 13 of 23 chants. His listeners heard touchstones of English musical heritage, including Tallis’s chant in F, services by William Boyce, and glorious anthems by Purcell, Maurice Greene and William Croft.

Reviving the gorgeous old music was risky, often criticised as a popish distraction from worship. Indeed, Temple Church Master Christopher Benson briefly stopped Calvert’s choral chanting until hundreds of barristers petitioned for its return, and the societies backed Calvert.

Calvert’s choir won immediate national coverage in over 50 newspapers. Press often named the music, said it was “very beautifully performed”, and that the double choir enhanced “the fine effect of the exquisitely harmonious chanting”. Congregations flocked in, over 20,000 in nine months. Royalty came and socialised with the Benchers – gratifyingly mentioned by the press – after Prince Albert dropped in to a rehearsal.

Calvert meant the Temple choir “to further the use and love of Cathedral Music in this country”. Writing while running the choir, he published two choir manuals in 1844. His Psalter explained the intricacies of choral chanting. His Collection of Anthems listed 900 works. Burge promised to have it published. Instead, he read Calvert’s draft, then published his own choir book first.

Calvert waded through choir politics, including months of bitter drama, to replace George Warne, the existing organist, with Edward Hopkins, who started on 25 May 1843. The societies were enthusiastic but new to choir management, so Calvert constantly had to explain the professional realities. The Benchers suggested singers; Calvert found they were unavailable, better paid elsewhere, or sang in “low taverns”! Burge managed Calvert, directing all music purchases and micromanaging rehearsals.

In May 1843, the societies fired the excellent, reliable tenor John Hobbs for a legitimate absence. Without Hobbs’ guidance, the inexperienced Calvert made mistakes.

In July, the societies pressed to hear music they did not own, so Calvert proposed a purchase list to Burge. In August, Burge gave verbal orders to spend £130 on music, nearly twice what had already been spent, promising reimbursement in November. Burge, knowing he had no such authority, left no paper trail.

To get the music in time for the new season, Calvert ran through his own cash, borrowed money, delayed some payments and quietly marked up a few prices. He submitted his bill in late October.

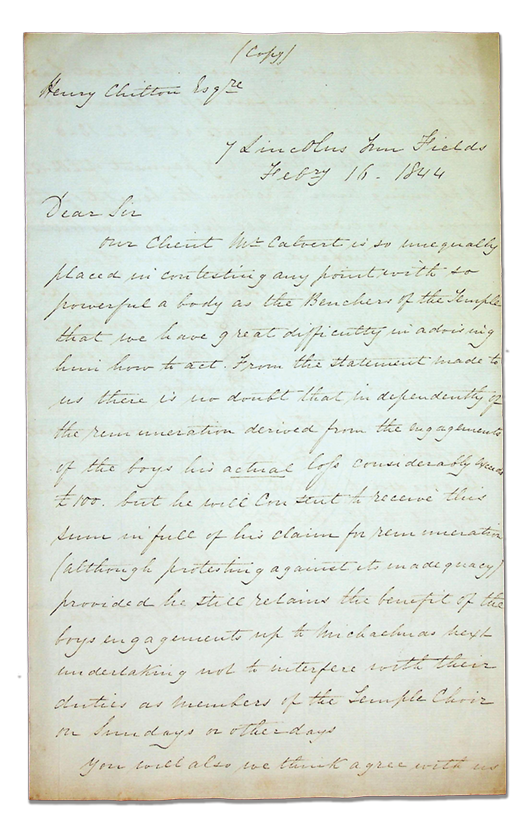

Startled, the Inner Temple Treasurer asked who had authorised it. Burge brazenly blamed Calvert. Without written orders, the Committee offered only partial reimbursement. Calvert furiously replied that he was too honest to lie and asked to prove Burge’s verbal orders.

An Inner Temple Bench examination of witnesses including Hopkins and Hawkins concluded that Calvert believed he had been properly authorised and directed the Committee to reimburse his actual costs.

Racing about to find “one volume here and another there” had left chaotic accounts. After exhaustive assessment, the societies paid Calvert £128 for music. He was saved! He wrote an incandescent (though unsuccessful) plea to reinstate Hobbs.

Fatally, he then embarrassed the societies. In January 1844, they discovered that he had told some singers and shops that he could not pay them because the societies had not paid his own salary. True enough, but only because he had not submitted the required salary receipts. It was over. The societies, scrupulously fair, paid £112 for early termination and allowed him to resign.

Tellingly, Calvert never blamed the societies, but only “the deceit and falsehood of Mr Burge whose conduct to me… has been one system of underhanded deception… So rests this piece of treachery til God who knows all hearts shall judge between us”.

Resolute, he sang every service until his last, on 11 February 1844. His final anthem was Boyce’s By the waters of Babylon I sat down and wept.

Four days later, the Morning Chronicle wrote, “The choir of the Temple church… is greatly superior to that of any other church in London, excepting the cathedrals…”. He handed his successor, Edward Hopkins, a permanent, well-trained choir with a big repertoire (that Hopkins used in 1844 and beyond), a music library, a choir room, permanent choir stalls, and – an unexpected legacy – crisper oversight by the societies. Hawkins, Hobbs and Cooper were gone, but with their help, Calvert’s Temple choir had restored a vast swathe of ancient music that endured in the nation’s devotional life. For example, in May 1857, 17 cathedrals performed 22 works from Calvert’s Temple repertoire. He had launched the musical vision of The Inner and Middle Temple.

The Temple job reshaped Calvert’s life but not his values. His devotion to music as the “glorious harmony of the starry world above” undimmed, in 1844 he started a choir for St James’s Cathedral, in Jamaica.

Kristina Guiguet

Independent Researcher