ICLR

If it's reportable, we report it.

At the time of preparing this edition of the Yearbook, the Inn learned of the sudden and untimely death of Master Catherine Callaghan. Master Callaghan had, a short while before her death, generously offered for publication in the Yearbook this study of the Temple Church West Door, a project close to her heart, especially because she and Andreas Gledhill were married there on 21 April 2018. Catherine was also a Trustee of the Temple Church Trust. We are most grateful to Andreas for his permission to publish Catherine’s article as a testament to her work – and are privileged to do so.

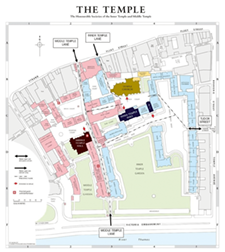

Temple Church is situated at the heart of legal London, in an enclosed enclave between Fleet Street and the Thames (Figure 1). The church serves as the collegiate chapel of The Inner and Middle Temples. But it was originally built as the main English church of the Knights Templar, the medieval religious-military order founded to protect pilgrims to the Holy Land. As they did elsewhere in Europe, the Templars built a round-naved church (Figures 2A–B), which was intended to recreate the Rotunda of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (Figure 3). At the western end of the round nave is the West Doorway, which is protected by a deep porch (Figures 5A–B).

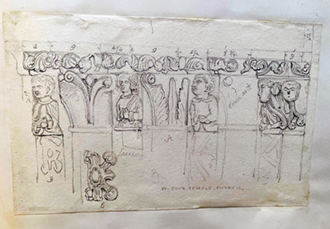

The West Doorway Is built of Caen stone from Normandy, a cream-coloured durable limestone. It is large and imposing, measuring approximately 4 metres high and 4.4 metres wide. It consists of a semi-circular Romanesque arch recessed in seven orders of alternating high-relief foliage carving and plain mouldings. The moulded arches spring from leaf-pattern capitals with plain columns below, while the carved arches sit above unusual half-figure busts, supported on shafts embellished with geometric and floral patterns (Figure 6).

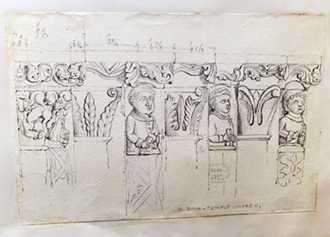

There are four busts on each side of the door. The busts on the north side are wearing caps or turbans, and several wear tunics with buttons down the front (Figure 7). Before the 14th century, buttons were not generally worn in England and were considered oriental, so these figures may have been intended to represent Muslim infidels whom the Templars were called to fight. The busts on the south side are bare-headed and may have been intended to represent Christians (Figure 8).

No foundation documentation survives, but scholars now date the construction of the round nave (and therefore the West Doorway) to circa 1160s based on documentary and architectural evidence. In 1161, the Knights Templar sold their initial London base in Holborn, which included a round church, to the Bishop of Lincoln, and relocated to the current Temple site, so the replacement round church is likely to have been useable by then. In 1163, the body of Geoffrey de Mandeville was buried in the cemetery or ‘the porch before the west door’ of the church. The first reference to a completed church appears in the Archbishop of York’s indulgence, issued sometime between 1164 and 1181. Christopher Wilson considers that the similarities between the foliage scrolls on the archivolts of the West Doorway and the scrolls on the hemicycle capitals at Dommartin in northern France (c 1153) are so strong that they are likely to have been made by the same sculptors.

ICLR

If it's reportable, we report it.

Trusted law reporting since 1865

The West Doorway, with its ornate and imported Norman stone, would have powerfully conveyed the wealth, status and French origins of the Knights Templar. Medieval visitors would have viewed the West Doorway as the gateway to a church that directly evoked the place of Christ’s death and resurrection, and indeed Jerusalem itself, the centre of the medieval world.

After the Knights Templar were suppressed in the early 14th century and their property was seized by the Crown, lawyers moved in to lease the Temple area. In 1608, King James I granted the freehold of the Temple area to The Inner and Middle Temple in perpetuity on condition that they maintain Temple Church at their own expense, a sign of its religious and historic value.

ICLR

If it's reportable, we report it.

Trusted law reporting since 1865

By the late 17th century, shops and lodgings had been built against and around the church, including under the porch against the West Doorway, suggesting it fell out of use and lost significance at this time. However, a revived interest in the early Gothic architecture of the church, together with the Inns’ concern to protect the fabric of the church and improve the urban environment, led to the removal of the adjacent buildings in the 1820s. The West Doorway was visible again!

From 1840 to 1843, Temple Church underwent a major restoration under architects Sydney Smirke and Decimus Burton, costing an eye-watering £70,000. In 1842, the architects reported that the carved arches on the West Doorway were “so perished as to be for the most part incapable of receiving reparations and … ought to be entirely new”. Surprisingly, their 1845 report on the church restoration contains no reference to any work carried out on the West Doorway. However, at least four original voussoirs from the arch of the West Doorway were removed during that period and subsequently donated to the Victoria & Albert Museum (Figures 9A–D). Recent investigations have found that at least the innermost order of the arch, the leaf-pattern capitals and the plain columns were rebuilt with Caen stone in the 1840s (Figure 10).

The Victorian restorers made two well-intentioned but ultimately disastrous interventions. First, they used Caen stone quarries of lower quality than those in use in the 12th century; as a result, the 19th century replacements decayed rapidly. Second, the entire doorway was then painted with white lead, presumably to unite the appearance of old and new stonework. The application of an impermeable lead-based paint caused “gross damage” to the stonework. Multiple treatments were applied to arrest the decay over the next hundred years.

On 10 May 1941, German incendiary bombs destroyed the roof and interior of Temple Church but left the West Doorway largely unscathed (Figures 11A–C). As a result, the doorway was untouched during the subsequent extensive restoration by Walter Godfrey. However, the wartime damage to the roof likely caused water ingress which further decayed the stonework.

By the 1980s, soot deposits combined with traditional treatments of hot oil or wax and limewash had resulted in an impervious skin of calcium sulphate with a build-up of moisture and chemical salts beneath. Where this skin had burst, more rapid decay set in. In 1984, the West Doorway was cleaned by air abrasive methods. In 1998, further cleaning was undertaken by laser.

Today, although much of the stone is in an advanced state of decay, the West Doorway retains a faded magnificence. The doorway and the church have become a tourist destination, particularly for fans of The Da Vinci Code. The doorway is used for special occasions, such as Call to the Bar ceremonies and weddings of members of Inner or Middle Temple (including the author) (Figure 12). As a result, it lives on in countless graduation and wedding photos.

Now the next chapter begins, as the Inns embark on a major programme of repair and restoration to the West Doorway, aimed at minimising the rate of decay, preserving the integrity of the 12th century carving, and re-introducing the West Doorway as the principal entrance to the church. Funding worth millions of pounds has been secured from the Inns and generous donors around the world, a mark of the doorway’s continued social and cultural significance.

Catherine Callaghan KC

1971–2025

For the full article with footnotes:

innertemple.org.uk/westdoorway