FOUR DISHES

EX DONO W W M 1864

Master Michael Lawson: This is the rather bland engraving on the bases of four curiously decorated, but beautiful, dishes in our collection. The announcement of William Mackeson’s death on 4 March 1892 is equally lacking in detail about the person, save that he was an Inner Temple barrister.

“On the 4th March at Lancaster, England, at the residence of his son-in-law, Lieutenant-Colonel Sidney Cargill, William Wyllys Mackeson, barrister-at-law, Bencher Inner Temple in his 80th Year.”

In fact, he enjoyed an interesting and multi-faceted life lived in Victorian times. He was the second son, born in August 1812, of his parents Captain John Mackeson and Olive (née McKeand), and one of five children. His delightfully named sister Delicia Jane married the Sidney Cargill mentioned above, then a Captain, in 1877. William’s father was a member of the brewing family, Mackeson, and that branch of the family lived on a coffee plantation on Blue Mountain in the parish of Manchester, Jamaica. William appears to have retained an active interest in local affairs throughout his life and is noted in 1845 as being a member of the Assembly and Standing Counsel for the Parish of Manchester, and later also of the Parish of St Ann, even after he had started practice in England. He was listed on the door of chambers in Spanish Town, Jamaica from 1836–1849. In 1887 he was listed as a Director of the Colonial Sugar Refining Company.

In 1843, William and David Smith, also coffee plantation owners, set up a private company to introduce railways to Jamaica soon after their introduction in England, naming the endeavour as the ‘Atmospheric Railway Project’, an ambitious venture to link the port of Kingston to Port Antonio on the north-east coast and Montego Bay in the north-west across the interior of the island.

William Mackeson was described as an “influential committee member”. The railway appears to have thrived and was bought by the Jamaican Government in 1879. In 1900, the government, with the assistance of American consortia, extended the network to complete the project. Initially used to transport people and agricultural produce, the railway later became the preferred method of transporting the Bauxite deposits, discovered in the 1940s, to the sea. It appears that the lines are now unused, although there are plans to use parts of the network as tourist attractions.

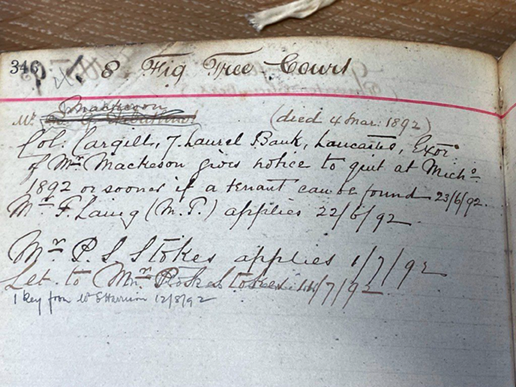

Mackeson was admitted to The Inner Temple in 1832, aged 19. He had gone up to Oxford aged 16 in March 1829. He graduated from Queen’s College in 1833 with a 3rd in Classical Honours and a 1st in Mathematical Honours and was Called to the Bar in 1836. From 1850–1885, he was a Chancery Practitioner at 1 New Square for most of his practising life but for a few years before his death he is listed as a being a tenant at 8, Fig Tree Court, paying £80 annual rent. His executor, Colonel Cargill, is given Notice to Quit by Michaelmas “or sooner if a tenant can be found”.

William Mackeson was listed as Patent Counsel in 1864 and took Silk in 1868. Little is known of the detailed nature of his practice. However, we know that he was the joint editor of the 5th Edition of Coote on Mortgage (1881) and of a text book on The Supreme Court of Judicature Acts 1873 and 1875, radical Acts which amalgamated the different courts of Common Law and Equity into one Supreme Court.

Another interest, revealed by our research, and probably prompted by his plantation experience, was slavery. In 1857, he was part of a seven-man delegation, led by Lord Salisbury, which petitioned Lord Palmerston to do more to end slavery and the slave trade, although it had already been abolished in the Empire by the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. He maintained that the trade was still carried out by France, Spain and Portugal using Cuba as their staging post. He argued that plantation owners were slave owners only because there was no other source of labour and that slavery could only be rooted out by African emigration treaties allowing Africans to leave their countries as free men. The Prime Minister is recorded as thanking the delegates for their thoughtful contributions, and stating that the government would give full consideration to their arguments and that it was committed to the crushing of the slave trade. Government responses do not appear to have altered greatly over time!

Mackeson was elected Treasurer in 1884. Inner Temple records only refer to correspondence during his year with barristers in Australia about the role of the Inns of Court in the English profession and, curiously, if they did not then have Inns of Court, an interest in a report on the conditions of ‘laundresses’ (ladies who looked after residential chambers) working in the Temple. At the end of his year, he generously gave the Inn the four silver dishes about which Richard Parsons writes more fully overleaf.

In 1857, he was part of a seven-man delegation, led by Lord Salisbury, which petitioned Lord Palmerston to do more to end slavery and the slave trade…

In March 1839, he married Ann, second daughter of Hugh Godfray, a Jersey resident. They had two sons and three daughters and lived at various addresses in the Paddington and Kensington areas of west London.

His name also appears in later years on the chessgames.com website as a member of the British Chess Club and a competition chess player, with six games for 1885 listed on their database. Sadly, he lost most of those games. In tournaments in London and Dublin he did rather better. He was also one of a team of eight Inner Templars who challenged a Dr Zukertort in The Inner Temple Hall. Dr Zuckertort was obviously a very remarkable chess player, although reputedly partial to laudanum, and played blindfolded throughout the six hours of play. He nevertheless won four games (including against Mackeson) and drew in three of them. One game was left unfinished.

Dr Zuckertort was of Polish origin and won the 1878 Paris Tournament and the 1883 International Tournament in London, after which he toured the US and Canada competing in simultaneous and blindfold exhibition matches. He obviously had a phenomenal memory.

The dishes remained in our collection until 1982 when the Executive Committee decided that some pieces had to be sold to finance a scholarship fund. We know that these dishes were bought by Master Woolf because he generously returned them to the Inn on his retirement as Lord Chief Justice in 2005. Having enjoyed them at his home he felt they should come back to their original home.

There is a pleasing coincidence that both the original donor, William Wyllys Mackeson – about whom we now know a little more – and the subsequent donor were both involved in momentous changes to our court system: Mackeson in explaining the Judicature Acts and Master Woolf in proposing equally substantial changes to our Civil Justice system in the Woolf Report 1996.

Richard Parsons: From time to time, a piece or group of silver objects appear on the market, or is viewed in a private collection, whose use or function is not immediately obvious. The set of four charming silver dishes in the Inn’s collection, made by James Fox in 1885/6, are an example. Oval in appearance the dishes are each raised on four small turtle feet, with shell form-edges, a scroll handle at one end and a Pegasus at the other. The Pegasus indicates that the dishes were made as a commission for The Inner Temple and their appearance gives an indication that they were made for some shellfish related food.

The maker, James Fox, was a member of a distinguished family of silversmiths who sold work directly to clients and worked for retailers. The dishes are also marked under the base with the retailers’ name of Lambert of Coventry Street, and it is likely that the dishes were commissioned from them, the manufacturing order being placed with James Fox, who was a regular supplier. The mark of other members of the Fox family and the retailer Lambert are found on a number of pieces in The Inner Temple collection suggesting that the two companies were employed as suppliers; for example the large Victorian rosewater dish of 1878, located in the Hall showcase and a reproduction of the 1563 silver gilt melon cup, copied in 1898, the original of which is also in the Hall display.

The functional answer for the dishes might be revealed by the shell sides which are scallop in appearance but not actual scallop shells. They more closely resemble a cockle shell, with a curved end but without the wedge end to the shell seen on a scallop shell. The dishes bear the London Assay Office date letters for 1885/6 and an inscription engraved underneath ‘EX DONO /WWM/1884’. Master Lawson gives details of the WWM initials in his interesting article, but the engraved date and the date of the dishes might lead to understanding their function. Master Lawson identifies the WWM as being for William Wyllyss Mackeson and also mentions that his chess playing took him to Dublin as a member of the British Chess Club.

If the shells are cockle shells, the chorus of the song Molly Malone “Cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh!” is part of a well-known song associated with Dublin. The song tells the fictional tale of a fish wife who plied her trade on the streets of Dublin by day (and was a part-time sex worker by night) who died of a fever as a young woman. At the time the dishes were made the Molly Malone song was published by Francis Brothers and Day, one of the leading publishers of music hall and popular songs of the time in London in 1884, as a work written and composed by James Yorkston, of Edinburgh with music arranged by Edmund Forman. The first verse of the song reads:

In Dublin’s fair city,

Where the girls are so pretty,

I first set my eyes on sweet Molly Malone,

As she wheeled her wheel-barrow,

Through streets broad and narrow,

Crying, “Cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh!”

Alive, alive, oh,

Alive, alive, oh,

Crying “Cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh”.

The dishes are quite small in size. Measured over the handles they have a length of slightly more than 12 inches and a width of 6.1/2 inches. They are large enough to receive scallops but would be better suited to the smaller cockle and are perfectly formed for table service. The traditional cooking method is to either boil or steam the cockles and serve them with vinegar and pepper.

By coincidence, the author was staying at St David’s in Pembrokeshire, South Wales a few weeks ago before taking a ferry to Ireland and at breakfast, apart from the usual table fare, was served an oval dish of cockles.

“Cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh!”

Richard Parsons

Jeweller and Silversmith

William Gallagher

The Silver team met on Friday 25 July for its summer inspection of the Inn’s silver collection. We did so with some anxiety as it was the first time we had gathered since William Gallagher’s retirement. He knew every piece, its catalogue number and who gave it to the Inn. He treated the items with such care, cleaning them and taking a selection of them up to Hall several times a month for dinners, returning them late in the evening before going home. He shared our concern if any piece was inadvertently damaged and identified them for us at our biannual silver counts. His love and care of the silver was in addition to his many other duties in the Inn which required him to arrive daily at 8.00am and work often till late.

We invited him back to join us for lunch to recognise over 30 years of stewardship of the Inn’s silver. We missed his help and cheerful banter in the morning but happily he gave us a hand to catch up after lunch. We noted how well he looked and that he had developed a taste for trips to Scotland to which he had previously never been. It was good to see him in such good spirits.

Thank you, William, for all that you have done for us – and the Inn – so brilliantly for many years.

His Honour Michael Lawson KC

Master of the Silver

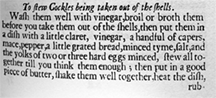

A 17th Century Menu for Cockles

For anyone who might like to try cockles, food historian Marc Meltonville has researched a possible 17th century menu found in the cookery book, The Accomplished Cook by Robert May.

He also prepared the 1660 recipe with fresh cockles, remarking that it was “Tasty but unremarkable, a little sharp for modern tastes”.