Marking Time: My Family and I

A book review by Master Rebecca Bailey-Harris

Sir Mathew Thorpe’s latest book is divided into two parts, at first glance seemingly distinct. The first is a record of his ancestors, the families of his four grandparents. The second part is Mathew’s autobiography – a long and colourful life of considerable distinction. A close reading of this book reveals the subtle connections between its component parts. The legacy of his ancestors has coloured aspects of Mathew’s own interests and achievements.

The first part is the history of four families. Mathew presents the reader with an extensive dramatis personae which paints a vivid picture of life and society in England and far beyond from the early 18th century onwards.

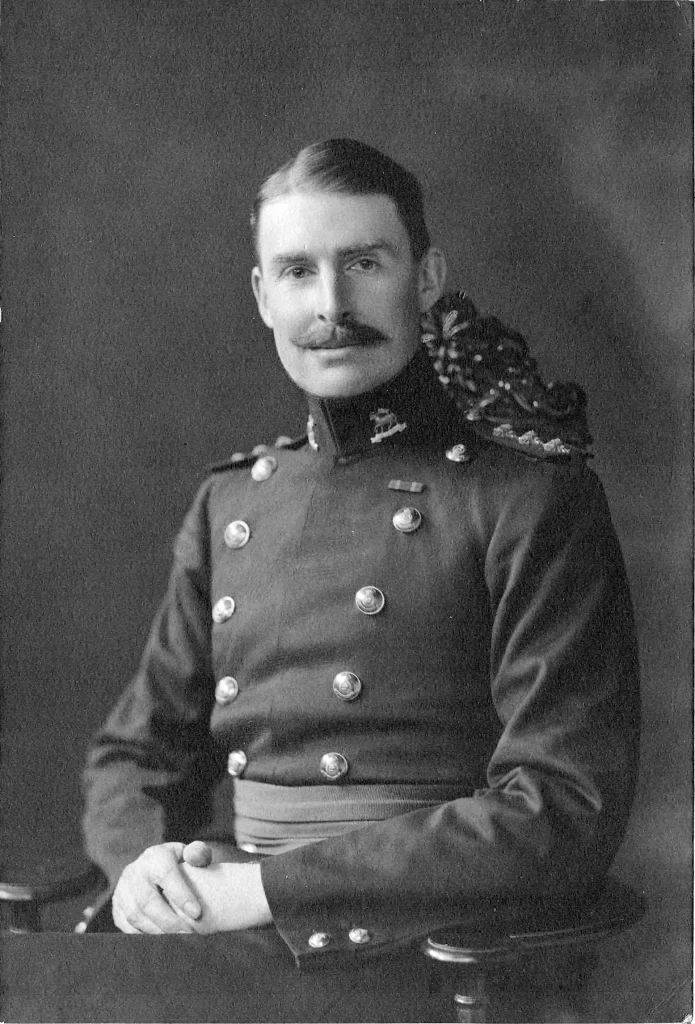

Of the Thorpe family, Mathew’s grandfather Captain John Somerled Thorpe fought in the Boer and First World wars and was killed in 1916. Mathew was particularly fond of his great uncle Gervase, a colourful character who spent many years in India and whose book recording the shooting of game there is as vivid as it is shocking to the modern reader.

The Meade family hailed originally from Ireland and then Ulster. John Meade, the First Earl, married one of the greatest Irish heiresses, but the fortune was squandered. Richard, the Second Earl, died at the age of 39, but his short life was significant for the time he spent in Vienna, where he married Countess Maria Carolina Thun. She died in childbirth in 1800. Her mother was a patroness of Mozart, who often performed music in her house. The Third Earl, another Richard, was described by Chateaubriand as “at the head of the London dandies”. In the diplomatic service he attended the Congress of Vienna and was described by a contemporary as being “as handsome at 70 as when Lawrence painted him 40 years before”.

Members of the Lambert family sought their fortunes in India and were successful in business enterprises there and in London. William (1836–1907) was engaged in the suppression of the Indian mutiny and in the Kaffir and Zulu wars in South Africa. Mathew’s grandfather, Colonel Arthur Lambert, served in the Dardanelles, writing letters in which he described one of the most dramatic theatres of the Great War. He was killed by a Turkish bullet and lies in the Gaza war cemetery, a particular poignancy in current times.

Of the Donaldson family, Mathew characterises Sir George as “a prodigy”. “Good looking, vain, self-important”, he nevertheless had “great flair” as a cultured man fluent in French and Italian. Sir George made his mark as a renowned collector and dealer, his special fields of interest being musical instruments, paintings, and furniture and decoration. His public spirit led to honours in Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, France, and England. Sir George’s collection of musical instruments was unequalled in Europe. The collection was gifted to the Royal College of Music and the State Opening of the Museum took place on 2 May 1894. Sir George gifted to the College the manuscript of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No 24 K 491 – “arguably the most important music manuscript in the UK”. As to art, he gifted Goya’s outstanding portrait of Doctor Peral to the National Gallery, and sold them Titian’s portrait of the poet Ariosto, at cost.

What themes can be traced from this rich ancestry into Mathew’s own life? I discerned the following: a love of shooting, an attachment to Vienna and Austria, interest in India, and more generally a marked internationalism. The reader may find other themes after perusing the second part of the book.

Mathew was born in 1938, when the “state of the nation was febrile as the threat of war with Hitler overhung”: the bombing of Petworth in September 1942 was a well-publicised disaster. Mathew gives a vivid account of stays in his childhood with Granny Thorpe at the beautiful Coombelands Estate. Mathew went as a boarder to Stowe in 1952: the house was dilapidated, and the magnificent grounds were in varying states of decay. Mathew was drawn to the study of history but “Classics was the only proper study for clever boys”. He sat the entrance examination for Balliol College, Oxford and was offered a place. The admissions tutor was as impressed by Mathew’s history paper as by his Latin. However, “for practical reasons” he chose to read law, “a subject in which Balliol excelled”.

Mathew’s account of his legal education at Oxford from 1957 is sparse because he was not attracted to the study of law as an academic discipline. The chapter on Oxford focuses instead on outings to Ascot and Goodwood, dinners at the Bell at Aston Clinton, parties given by “all the faster young ones”, shooting and poaching “under the wide Otmoor skies” and the decadence of the Annandale dining club. Mathew’s ‘Waterloo’ was the Honours School of Jurisprudence in 1960, receiving a third class degree. Following Oxford, Mathew and his friend Robert Douglas-Miller spent an interlude in India, using their connections with the “princely class” (including maharajas) to embark on game hunting and hopefully to bring back antique European weapons. They found “a sporting tradition on the point of extinction”, but Mathew was left with an affection for India and Indians. A less fortunate legacy was tuberculosis, which slowly incubated for four years and required Mathew’s hospitalisation for nine months.

Mathew’s self-awareness is telling: “Only when I moved from the study of law to the practice of advocacy did I become engaged and inspired.” After pupillage at 1 Mitre Court, he was taken on in 1962, initially earning paltry fees. This chamber ‘married’ Joseph Jackson’s set from Paper Buildings in 1969, a development of significance. In 1967, Mathew married Vina and in due course, Gervase, Al, and Marcus were born (to whom this book is dedicated). Life at Seend Green House was rich and varied; a major achievement was the restoration of the walled garden. Mathew continued his passion for horse racing and betting in partnership with David Oldrey and they owned racehorses from 1963 onwards. Breeding followed: the Seend Stud operated for 16 golden years until a long and painful process of liquidation set in.

Family law practice changed greatly with the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973. Mathew recounts that “a rejuvenated Family Division burgeoned on what was labelled ancillary relief litigation and I was perfectly placed to feature in the front rank”. He took silk in 1980, and thereafter was “at the zenith as an advocate”. The following eight years were “the exciting years of my prime, one high profile case following another”. These included Jagger, Guinness, Lady Radnor and the Contesse de Dampierre. Particularly engaging is Mathew’s account of a case in Hong Kong in which his client dispensed with his services and acted in person, it having been discovered that she had a Chinese cohabitant whom she subsequently murdered, dismembered, and buried in the garden. Mathew’s greatest public responsibility in silk was as counsel to the Cleveland Enquiry into Child Sexual Abuse from 1987.

Sir Mathew Thorpe’s latest book is divided into two parts, at first glance seemingly distinct. The first is a record of his ancestors, the families of his four grandparents. The second part is Mathew’s autobiography – a long and colourful life of considerable distinction.

Mathew’s appointment to the Family Division in 1988 marked a great change, not only in profession but in personal life. His marriage with Vina ended, Beech House was purchased and he married Carola. “Suddenly, I took on responsibility to the State.” Perceptively, Mathew observes that as a judge “I needed profounder understanding of human behaviour and psychology”. But he did not confine himself to the judicial function. Judicial activism, in striving to improve the quality of justice, was a radical departure from tradition. Mathew’s significant contributions of longstanding significance were to the Dartington conferences, the Ancillary Relief Working Party, and above all, to international family justice. The Court of Appeal followed from 1995 to 2013. In due course, as presider “my court became the principal vehicle for the carriage of family business”. But wider horizons beckoned. Mathew became the first Head of International Family Justice in 2005. He rightly regards his rich and varied experience “in creating a new field of judicial practice and in advancing British interests and standards across the world”.

The final chapter of Mathew’s autobiography is tinged with sadness: disappointment at not been given, after retirement from the bench, the work in ADR which his talent merited. But the final page of his autobiography is joyful. Mathew announces his engagement to Aleksandra, whom readers of A Divided Heart will know. We readers wish them every happiness for the future.

Rebecca Bailey-Harris

1 Hare Court

Available from the author at thorpe@1hc.com at £25 p&p included or at £20 collected from 1 Hare Court