Three Treasures from the Library

History Society Lecture

From a lecture delivered on 26 July 2023

One

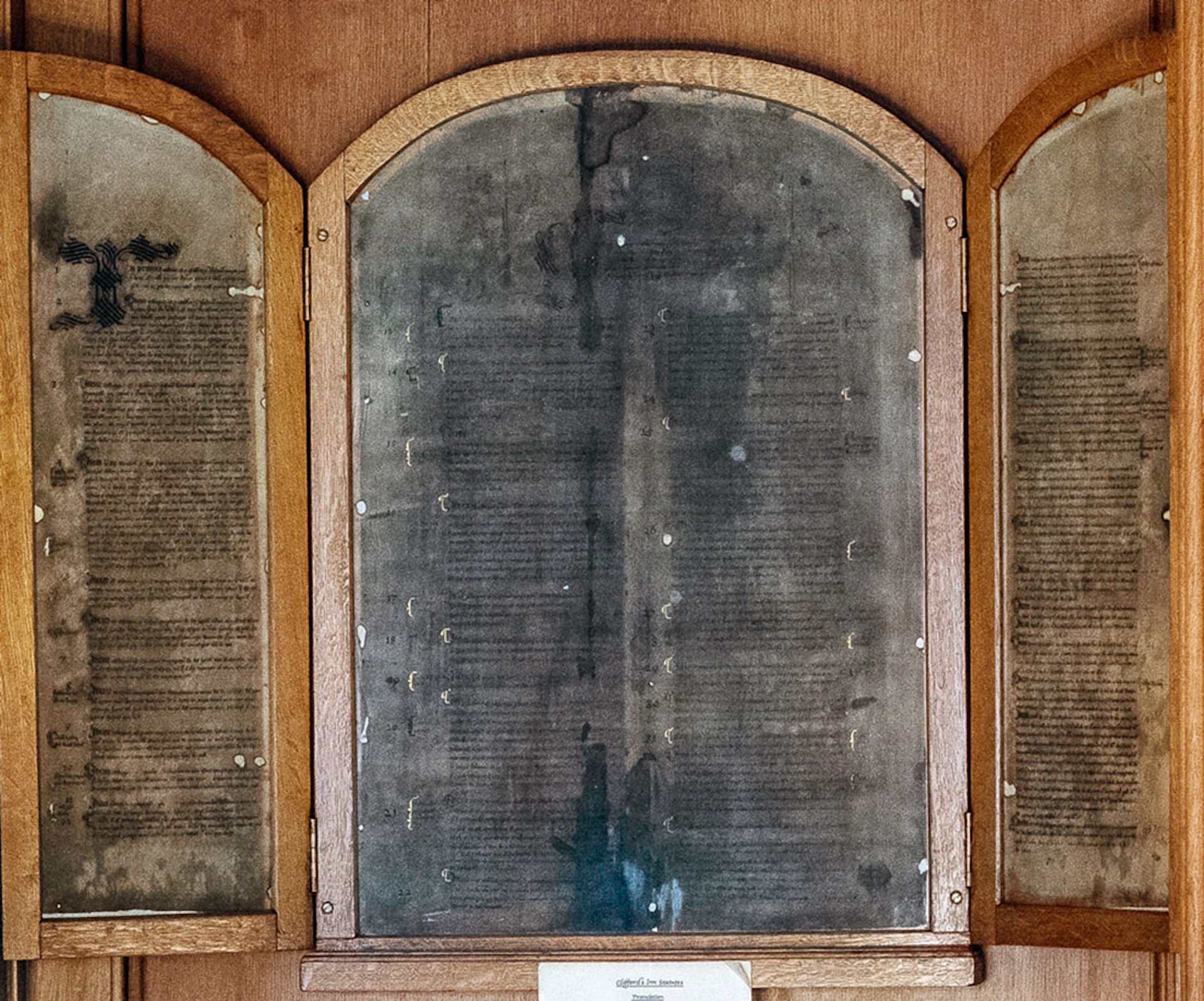

The Clifford’s Inn triptych is a unique link with medieval legal education. The Inns of Court and Chancery probably came into existence around 1340, when the legal profession returned en masse from a five-year exile in York. Clifford’s Inn was the earliest of all the Inns to be mentioned specifically in surviving records (in 1344). It took its name from the owner of the freehold, Lord de Clifford. When the society was dissolved in 1903, some of the armorial windows were placed in The Inner Temple Library, and a minute-book from 1610 to 1740 (the oldest from any of the Inns of Chancery) was also given to the Library; all were destroyed by enemy action in 1941. Two other windows survive in the Judge’s Room of the Mayor’s and City of London Court, one with the arms of William Skrene, who was called to be a serjeant in 1396 directly from Clifford’s Inn – sometimes treated as evidence that it was once an Inn of Court.

The medieval hall of Clifford’s Inn was demolished by developers in 1934 and is said to have been taken (in pieces) to America. (Where is it now?) But the triptych with the ancient statutes of the Inn, which had hung in the hall for nearly 300 years, had already been transferred to the Inner Temple in 1903 and survived. As long ago as 1800 it was said to be scarcely legible, and in 1902 Hay-Edwards (in his history of the Inn) said that nothing of the writing remained except the illuminated capital letters. In fact – grimy and faded though it is – the text can nearly all be read. There are four columns containing 47 numbered paragraphs, written in law French, with the Tudor royal arms at the head.

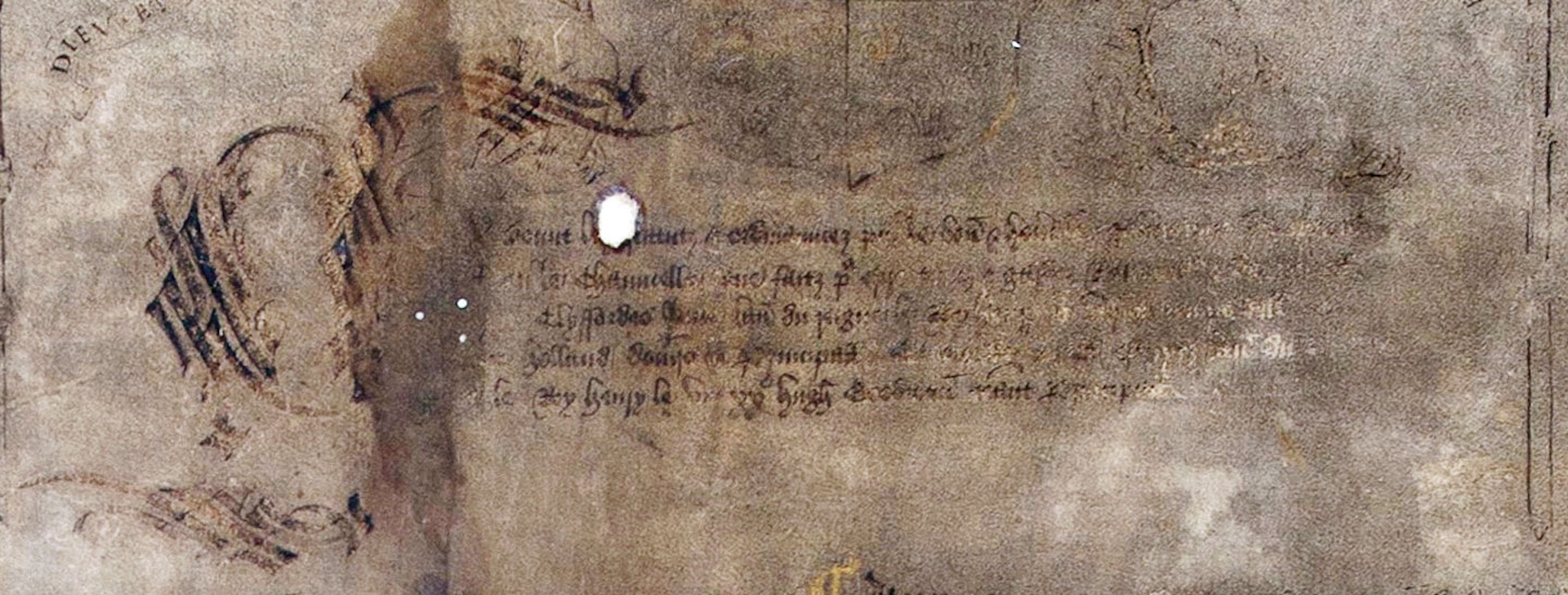

The caption is the most badly damaged part, and some crucial words are lost, but almost all the missing text can be supplied from a 17th century transcript found in a solicitor’s office in Brick Court in 1998. Translated into English, it reads:

“These are the statutes and ordinances made to be held and kept for the good and honourable governance of the new Inn in ‘Chancellor Lane’, renewed and newly written in Clifford’s Inn in the [twenty-something] year of King Henry VII, in the time of Lawrence Holland, then principal there, and now newly written in the twentieth year of King Henry VIII, Hugh Goodman being principal”.

Holland was principal from 1504 to about 1510, and so the ‘renewal’ must date from about 20 years before the engrossment on vellum in 1528 or 1529. Whatever renewal meant, it does not seem to have involved much editorial work. The text is in no rational order and seems to be a random compilation of orders made at different times. Statute 20 is actually dated 1478 and must be an addition to an earlier code. Statute 24 forbids the playing of ‘new fair’, a gambling game otherwise known only from Langland’s Piers Plowman, written in the late 1300s. So, the earliest of the statutes may even date from before 1400.

The caption contains an unsolved puzzle. It tells us that the renewal was made in Clifford’s Inn. But the preceding words, only recently deciphered, say that the original statutes and ordinances were made for the “new inn in Chancellor’s Lane”. What, then, was this ‘new inn’? Was it the society set up in Lord de Clifford’s house in the 1340s? Does ‘new’ here refer to the 1340s? Clifford’s Inn certainly had an entrance in Chancery Lane. But there was a different inn further up the lane, facing what is now Lincoln’s Inn. This was from 1353 to 1374 the house of John of Tamworth, a Master in Chancery, and was used for training Chancery clerks. Sometimes called Tamworth’s Inn, it was also by 1368 called the New Inn. References to the New Inn in Chancellor’s Lane have recently been found from 1412 and 1429, by which time Clifford’s Inn was known by that name. (To confuse matters, there was also an Inn of Chancery near the Aldwych called New Inn – which, like Clifford’s Inn, survived into the 20th century). Tamworth’s Inn never became an Inn of Chancery in the later sense, and we do not know for certain why the lesser Inns were so called. Medieval Chancery clerks were supposed to be trained in the Lord Chancellor’s household, or in the households of the masters (the 12 senior clerks, headed by the Master of the Rolls) – and Tamworth’s Inn was one such. They had nothing much to do with the Court of Chancery – the Chancery was first and foremost the royal secretariat. Oddly, however, the eight Inns of Chancery which survived are not known to have begun in that way. Possibly some originally had Chancery masters in control. Clifford’s Inn did have a few Chancery clerks among its senior members in the 15th century, but they were a minority. It is more telling that the 1344 reference to the Inn mentioned ‘apprentices’, the name used for students of the common law and not for clerks learning to serve the Chancery – who were actually forbidden to mix with apprentices. The so-called Inns of Chancery all educated young students of common law, though the Lord Chancellor exercised some kind of control over them. How that superintendence came about is obscure. There may have been some analogy with university chancellors. More likely it recalled an earlier world in which senior Chancery clerks such as Tamworth had given lectures on the writs – the starting point of all legal study. By the early 1500s that world was long gone, and the Chancellor surrendered his supervisory role to the Inns of Court. Clifford’s Inn, together with Clement’s Inn and Lyons Inn, then became attached to the Inner Temple.

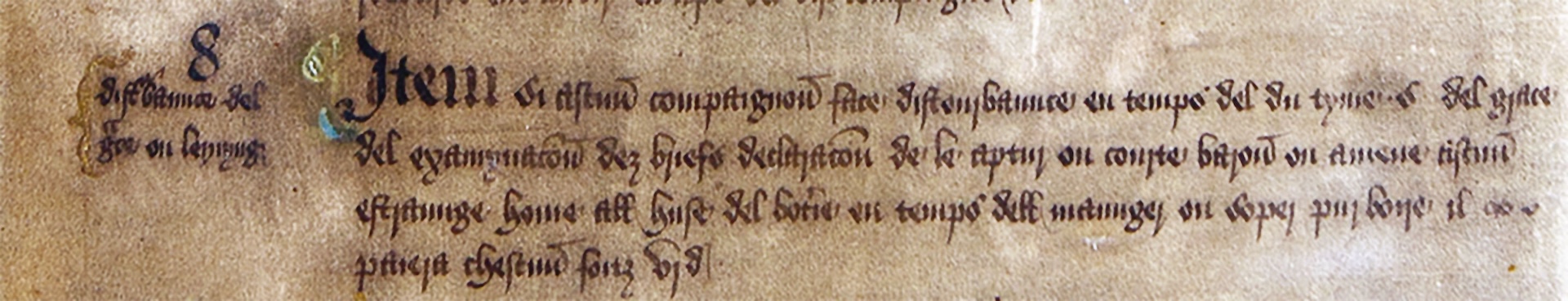

I will leave the puzzle there and return to the statutes. The glimmers of light which they shed on the educational system are slight, though it is the earliest light we have. In statute 9 there is a reference to “learning according to the custom of the court”. Everyone knew what that was, so it isn’t spelt out; but ‘custom of the court’ is an intriguing expression in this context. Statute 8, dealing with disorders, mentions three learning exercises: “the examination of the writs”, “the declaration of the opening (?)” and “court baron”. It seems likely that the first and last correspond with the 14th-century treatises Natura Brevium and Curia Baronum, which began as lectures. Statute 40, probably of later date, mentions four exercises: writ-reading, lecture, moot and report. It also refers to the Reader of the Inn. The fines laid down for defaulting show that moots were considered the most important exercise, whereas missing the writ-reading – perhaps a passage from the Natura Brevium – only cost 6d. The penultimate chapter, probably a Tudor addition, refers to utter and inner barristers. As in the Inns of Court, these ranks related originally to mooting; an utter barrister was a member who had been called up to argue a moot at the bar of his Inn. But a barrister of an Inn of Chancery had no standing outside it; to acquire a right of audience in courts of law he had to progress to an Inn of Court, and again graduate from inner barrister to utter barrister by performing a moot.

Like so many codes, the statutes omit to tell us what everyone knew. Written regulation was needed only for the minutiae of governance and discipline. Of this we learn quite a lot. The members were called compaignons (fellows). There were no admission qualifications, save that a fellow had to find two sureties, had to be able to pay his pension (a room-rent of 3s or more), his commons and dues, and 13d for his pewter plate and saucer. Fellows took it in turns to be steward for a week, unless excused (on payment of 1s). The steward was responsible for the cloths, cups and salts, for buying bread and ale, for shutting the gates at night, and for reporting anyone who came in after the gates were shut. The Inn had a principal, and the principal had a council (later known as the ‘ancients’). Fellows were forbidden to “make construction” of the statutes against the principal and council, or to plot or compass the removal of the principal without the consent of the council. Speaking opprobrious words of the principal resulted in expulsion from commons.

There were several rules about commons. Any pensioner spotted between St Paul’s and Temple Bar was deemed to be in commons and charged for meals, whether or not he ate them; other members might be charged for ‘repasts’ (meals paid for separately). Drink was available at the buttery during dinner and supper, but strangers were not to be introduced, on pain of 6d. Attendance during Christmas was compulsory for two years after admittance, and the 1478 order mentions the election of a Christmas marshal to oversee festivities

We know that the students, who were mostly from gentry families, were aged about 18 on admission, and we find paternalistic measures in Clifford’s Inn such as the rule that they should not mortgage their hutches (ie trunks with their belongings) or enter into usurious loans. Minimum standards of behaviour were required. Fellows were not to disgrace the Inn by going out to pursue vendettas, or by bringing in women of ill repute; such major offences incurred a fine of 6s 8d. Breaking down the buttery door, or procuring it to be opened “by art or engine”, cost 12d, doubled for a second offence, with expulsion for a third – drink was in high demand. Fellows were not to speak ribaldry in Hall, on pain of a farthing a word. Causing an argument – not a legal argument, that is – cost 6d. They were not to play tennis, dice, cards or quoits, or to keep greyhounds, spaniels or mastiffs. For drawing a knife or sword in play, the penalty was only 1d a time, though striking another with fist, staff, knife, dagger or other object, cost 12d (provided no blood was drawn) besides amends to the victim. (Evidently, kicking or throttling were not foreseen.) Bloodshed meant a fine of 6s 8d and expulsion. Drawing a weapon in anger on another fellow, or on the cook, also merited expulsion. These regulations evoke the violence and misrule which were endemic in a community of young students far from home, without tutorial oversight.

Similar regulations were in due course made for the other inns of chancery. But the old statutes of Clifford’s Inn, even if we cannot precisely pick apart and date the component elements, include within them the remains of the earliest written regulations for any of the legal inns and provide a vivid insight into student life in these medieval societies.

Two

The four beautiful illustrations of the 15th century courts take us from Chancery Lane to the more exalted atmosphere of Westminster Hall. They were excised from an abridgment (or digest) of cases written around 1450–53. We know it was an abridgment because the slightly smaller Common Pleas picture on the first page has beneath it (and on the verso) the beginning of an alphabetical index of the titles. And the date may be calculated from the depiction of seven judges sitting in that court, something which only happened between Michaelmas 1450 and June 1453.

These priceless paintings, though ignored by art historians, are a landmark in the history of English secular art. They are also the earliest pictures of English law courts in action. Indeed, they are the only coloured representations of the principal courts before the 18th century. They were presented by Master Darling, Treasurer in 1914. All we know of their provenance is that in 1860 they belonged to Selby Lowndes of Whaddon Hall, Buckinghamshire. His ancestor William Fleetwood (d 1594), Serjeant-at-Law and Recorder of London, was a collector of fine legal manuscripts. It was also pointed out in 1860 that the antiquary Browne Willis (a member of the Inner Temple) lived at Whaddon Hall until his death in 1760. But Willis’s manuscripts were left to the Bodleian Library and are still there (110 in number). I can throw in a third connection. Whaddon Hall belonged in the time of Henry VIII to Thomas Pigot, Reader of the Inner Temple in 1501, later a King’s Serjeant. Serjeant Pigot owned a fine illuminated statute-book, now in the Bodleian Library, and so he obviously liked expensive books. But whether any of these owned the manuscript is unknown.

The Whaddon Hall volume must have been commissioned for a significant person in the law. Abridgments were a new invention in 1450, and this was one of the first. None of the others which have survived contain any pictures. Indeed, no other English legal manuscripts have full-page illustrations, and most have no adornment at all. The only other decorated law books in the period are the showpiece statute-books on vellum, such as Serjeant Pigot’s, which often have initial letters with pictures of a king sitting in parliament. That is a genre well known to art historians. But the little miniatures do not contain anything approaching the level of detail found in the Whaddon Hall manuscript. They do not even show us what the House of Lords looked like. The closest comparator is the full-page picture in the Mayor of Bristol’s Calendar by Robert Ricaut, town clerk, which shows a mayor taking the oath of office in the town’s council chamber: the concept is similar, though the painting is less accomplished and a quarter of a century later in date (1479).

I will say a little about each of the miniatures in turn. The Common Pleas was on the front page because, though formally inferior to the King’s Bench, it was the most important of the four courts in terms of business. The judges are sitting on a raised bench beneath a blue cloth of estate with the royal arms flanked by the arms of Edward the Confessor (founder of the palace in which they sat) and England. In front of the judges is a huge table covered with green cloth, and outside that (in the foreground) a substantial bar – an oak barrier at least four feet in height. The court is a scene of activity. Around the table, on all four sides, sit the various clerks with their parchment rolls, pen-cases and inkwells, and a book bound in red (probably a Bible for swearing jurors and witnesses). If they were all present, there would have been at least 20 clerks: the three chief clerks (called prothonotaries), who kept the rolls with pleadings and judgments; the thirteen filacers, who kept rolls recording mesne process; and the four exigenters, who enrolled process leading to outlawry. On the massive table stand two criers or ushers holding short tipstaves. At the bar a dishevelled and poorly dressed defendant has been brought up in the custody of the warden of the Fleet Prison, who is armed with a cutlass and carries a long staff. To the sides are five serjeants-at-law, one of whom at bottom left is taking instructions from a bare-headed attorney. Only serjeants-at-law had rights of audience in this court: indeed, they originated as the Bar of the Common Pleas. It is to be noted that the judges have no desks, or anywhere to put papers, and that the serjeants (who stand outside the bar) do not even have seats. There are no books or bundles of papers, just the Latin pleadings in the rolls. The mere threat to produce a book could be enough to defeat a shaky argument.

The serjeants and judges all wear the white linen coif, tied under the chin. Serjeants-at-law were invested with these by the Lord Chief Justice upon their creation and constituted a select order of dignity, known unofficially as the ‘order of the coif’. The judges are wearing essentially the same robes that judges still wear on ceremonial occasions: a robe, a hood around the shoulders, and over that a mantle, all of fine scarlet cloth faced with miniver. The serjeants, junior counsel, clerks and ushers all wear long parti-coloured robes, one side being of plain cloth and the other cloth of ray (that is, striped). Four of the clerks are wearing the Lancastrian livery colours of blue and white, whereas all the serjeants in this and the other pictures have blue and green. Later in the century the serjeants adopted the blue and mulberry colours of the House of York, which are also evident in the Bristol miniature. The serjeants are distinguished from lesser members of the Bar not only by their coifs but by wearing hoods.

If we move on to the King’s Bench, the scene is not dissimilar, though there are only five judges and a criminal trial is about to begin. The defendant has been brought up in the custody of the marshal, similarly armed to the warden of the Fleet, and is raising his hand on arraignment. To the left of the picture, a crier (in the Lancastrian colours) is handing the Bible to the jurors as they are sworn. Here there are only two serjeants, which is unsurprising since defendants indicted for treason, murder or felony were not allowed counsel. In the foreground we see a sorry group of prisoners awaiting trial, some of them with hardly any clothes. They are chained at the ankles, as indeed is the prisoner at the bar, despite the assertion by legal authorities such as Bracton that shackles were to be removed on arraignment. Only a few years ago this very picture was cited in America to counter the written authorities and justify the continued practice (in some states) of shackling defendants in court.

The Court of Exchequer presents a different scene. There is as yet no chequered table, though there are gold coins being counted, and banded coffers of treasure on the floor. The lock-up in the foreground is a surprising feature, but no doubt the king’s debtors were a slippery set; being kept in a box was (I suppose) slightly less degrading than being chained. Here there are three serjeants, but also three counsel without coifs – apprentices of the law (still not called barristers). One of the apprentices is raising a bag of coins, presumably to stave off execution and have his client discharged. Only the Chief Baron has scarlet robes. That is because he was a serjeant: Piers Arderne, a former Bencher of the Inner Temple – his arms can still be seen over the fireplace in the old buttery. He was concurrently one of the Common Pleas judges, so he must have nipped across from page 1. The other judges have undyed robes of the same pattern. All five wear curious hats like those worn by chefs. This seems to have been a passing legal fashion.

Finally, we come to the Court of Chancery, where we are in an even more different world. The judges here are tonsured clerics. The Chancellor, who is covered, is John Kemp, Cardinal Archbishop of York. He is wearing the scarlet cope of a doctor of law, being an Oxford law graduate who had practised in the Church courts and served as Dean of the Arches. The Master of the Rolls, also in scarlet, and reading a patent, is John Kirkby. He is wearing different robes, more like those of the judges. The four Masters in Chancery have undyed robes; their hoods are cast round their necks scarfwise, a mode of wearing hoods which lives on at Cambridge when the proctors wear their hoods ‘squared’. The Chancery literally smelt of parchment and wax, and on the table we see the chafewax with his rolling pin, pressing the matrix of the great seal on to a warm seal attached to a charter. There is also a little pile of writs waiting to be sealed. The picture suggests that these activities still took place in open court: in later centuries the seal was carried into court ceremonially, in its embroidered burse, but the wax was chafed elsewhere. (They now use plastic granules and a hydraulic press.) At the bar there are three serjeants and two apprentices. That is significant: although the Chancellor was a canon lawyer, this was not an ecclesiastical court and doctors of law had no rights of audience. Another interesting feature is the group of five characters in the foreground, perhaps instructing attorneys waiting to furnish counsel with information when required.

The four miniatures were published as coloured lithographs by the Society of Antiquaries in 1864, with a slightly antiquated commentary written in 1860 by George Richard Corner (d 1863), solicitor and antiquary. They were privately republished by the Inner Temple in 1909, with Corner’s commentary but with photogravures in black and white. I would strongly recommend that they be published again, from colour photographs, so that their glorious details may be more widely known and understood.

Three

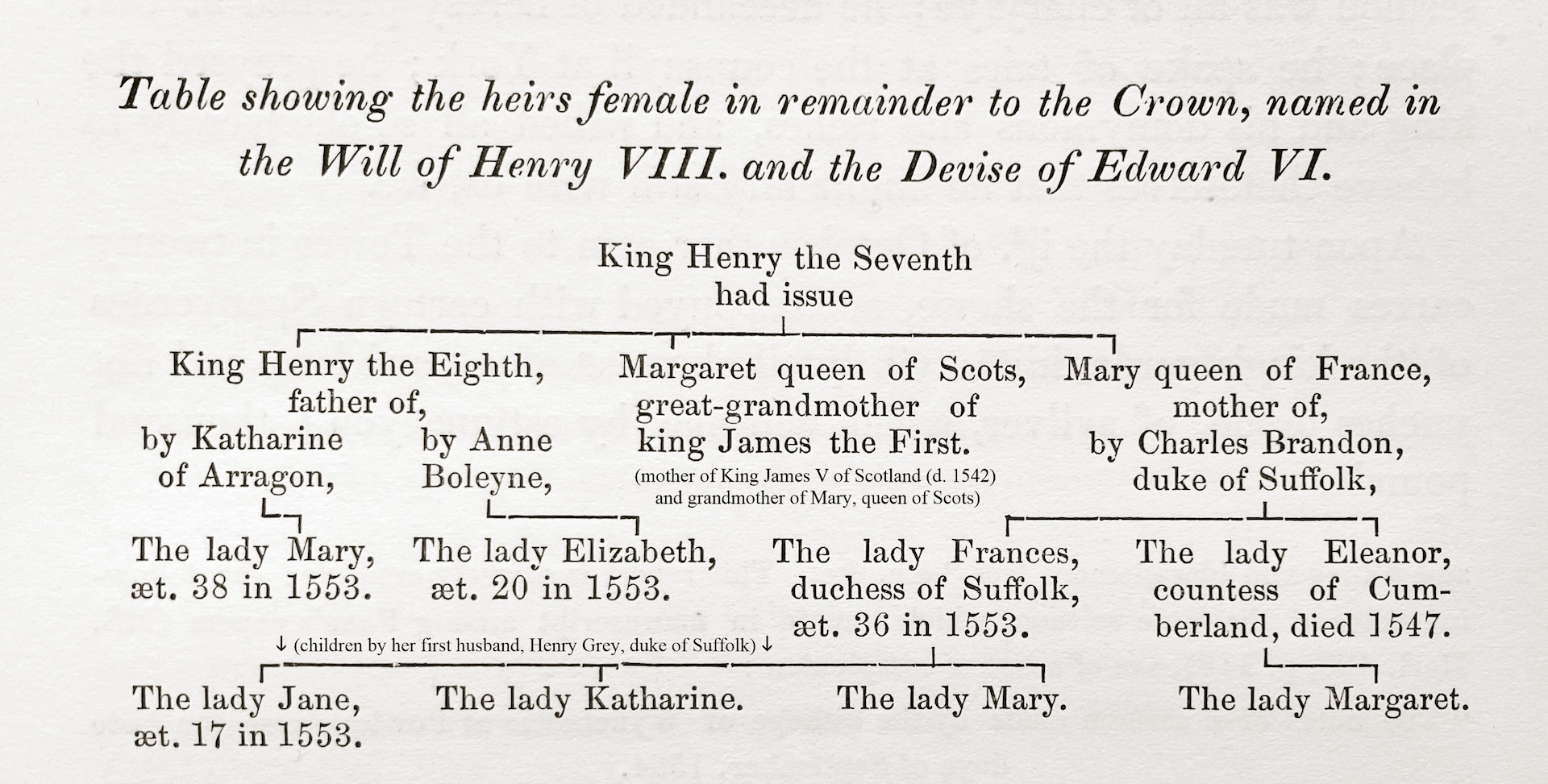

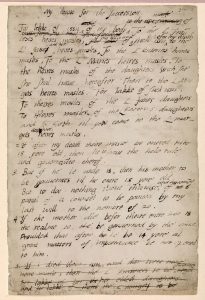

The third treasure is a remarkable document, one of the many manuscript treasures left to the Inn in 1707 by Master William Petyt. It is written in the hand of King Edward VI, who headed it “My devise for the succession”, and it is bound up with an undertaking signed by members of the Privy Council to support his scheme. It is thought to date from the time of the King’s final illness in 1553, when he was aged 15. To explain its significance, I will have to outline the genealogical background.

The succession to the crown had been thrown into some confusion by Henry VIII’s ‘divorces’ (annulments). His first wife, Katherine of Aragon, was the widow of his deceased brother Arthur; and the marriage had taken place with a papal dispensation from the impediment of affinity. After 24 years of marriage, Henry decided that their failure to produce a male heir was God’s punishment for breaking divine law, as revealed in Leviticus, a law with which even a pope could not dispense. In this country the law was not changed until 1921, and even then amidst much controversy. I am not sure I understand the objection: the text forbids having sex with a brother’s wife; it says nothing about a deceased brother; and there is a text in Deuteronomy which refers to a duty to marry a deceased brother’s widow. Anyway, Henry thereafter referred to Katherine as his “dear sister” and, after collecting opinions from numerous law faculties, decided he was free to marry Anne Boleyn; this was confirmed by Archbishop Cranmer. The effect of the divorce was to bastardise Princess Mary (who later had Cranmer burned to death). Three years later, the marriage to Anne Boleyn was also annulled, this time because of the King’s prior fling with Mary Boleyn. (The impediment of affinity was based on sex rather than marriage.) The effect of this divorce was to bastardise Princess Elizabeth. Assuming these divorces were valid, Henry’s only legitimate child was Prince Edward (son of Jane Seymour), who – as a male – would have become King anyway. The problem was, what should happen if Edward had no children, as by 1553 seemed certain.

Edward’s father (Henry VIII) had given the matter careful thought three years before his death. He decided to reinstate his daughters. That required legislation, since they were no longer legally his children. An Act of Parliament was passed in 1544 providing that if Edward died without issue the crown should go to Mary and her male issue, remainder to Elizabeth and her male issue, remainder (in case they had no male heirs – which, in the event, they did not) to such persons as the king should appoint by will under his hand. The next potential heirs were the Scottish line descended from Henry VIII’s sister Margaret, queen of King James IV of Scotland, and grandmother of Mary, Queen of Scots. But Henry’s will passed over that foreign line and appointed the remainder to the issue of his deceased younger sister Mary, Dowager Queen of France and Duchess of Suffolk. That meant the crown would go (failing Mary and Elizabeth and any issue they had) to the issue of Mary’s elder daughter Frances, Duchess of Suffolk, failing whom, the heirs of Mary’s younger daughter Eleanor, Countess of Cumberland. The arrangement had parliamentary sanction, as a form of delegated legislation, though a great debate arose in the 1560s as to whether Henry’s will had in fact been signed with the king’s sign manual, in accordance with the Act, or by a stamp with a facsimile signature – the king having become almost incapable of writing. But that is another story.

Edward VI and his advisers were not happy with Henry VIII’s scheme. They took the view that the annulments of Henry’s first two marriages were applications of the law of God; and it was therefore contrary to the law of God for his illegitimate sisters Mary and Elizabeth to inherit the throne. They also took the view that half-sisters could not inherit from Edward as children of the half-blood (that is, by different mothers). It was the common law (not altered until 1833) that children of the half-blood could not inherit real property from each other. Thirdly, they took the view that Mary, Queen of Scots, could not inherit because she was born in Scotland and was therefore an alien. It was also the common law (operative until 1870) that an alien was incapable of owning freehold property in England. These were strong arguments, if the descent of the crown was governed by the same rules as the descent of land, which generally it had been.

With all this in mind, in April or May 1553 Edward produced the ‘devise’ (device) in his own handwriting; and a more detailed revision of the scheme was prepared by lawyers in an unsealed document dated 21 June 1553, signed by the privy councillors and most of the peerage. The latter was hastily suppressed later in the year and remained hidden away until 1611 when Sir Robert Cotton gave it to James I to be destroyed. (Fortunately for historians, someone kept a copy, now in the British Library). Edward’s scheme, following the logic of the common law, was to exclude the Princesses Mary and Elizabeth, and the alien Queen Mary of Scotland, and move directly to the Suffolk line. As a further embellishment, he thought it a good idea to exclude women altogether. His device therefore limited the succession to the male heirs of Frances, Duchess of Suffolk, remainder to the male heirs of Frances’s daughter Jane, remainder to the male heirs of Frances’s second daughter Katherine and third daughter Mary, remainder to the male heirs of their respective daughters. Although England had never had a queen regnant, if we discount the Empress Matilda, most of the potential heirs were now female and so for the first time an attempt was made to exclude them all on grounds of gender. This was a legally questionable course. It was not only contrary to Henry VIII’s Act of Parliament, it was also contrary to the common law. Land could only be settled on male heirs – so as to exclude women – by means of an entail, a device founded on a statute of 1285 which did not apply to the crown. It was also an impossible course, for a different reason.

By the end of May 1553, it was obvious that Edward, now in palliative care on opiates, had only weeks to live. A crucial change was then made in the device, which may be seen in our manuscript. The King – if it is indeed his hand – altered “Lady Jane’s heirs male” to “Lady Jane and her heirs male”. The Duke of Northumberland may have been behind this. He held considerable sway over the young king and the Council, and in the very same month (May 1553) Jane Grey had become his daughter-in-law after marrying Lord Guildford Dudley. But there was a practical necessity for the change. Jane, only just married, had no issue. If the king died imminently, none of the male heirs enumerated in the device would yet have come into being; there would only be women. The whole device would therefore have failed. So, the tiny alteration brought a legitimate living person – inescapably, a woman – into the succession. It would prove to be Lady Jane Grey’s death warrant.

The other Petyt manuscript, which accompanied the king’s device, was signed by 20 members of the Privy Council and the law officers. The most prominent legal signatories were Sir Edward Montagu, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, and Sir John Baker, Bencher of the Inner Temple and Chancellor of the Exchequer. Montagu CJ was worried that the device contravened the statute of 1544, especially since a statute of 1547 (passed by Edward VI’s first parliament) declared that any claim to the throne contrary to the 1544 Act was high treason in all those who supported it. Montagu arranged a meeting of all the judges in Ely House, and they confirmed that support for the king’s project would indeed be treasonable. (Alterations in the succession always faced this problem, in that they amounted to high treason until they were embodied in legislation.) When Montagu reported the judges’ opinion to the Privy Council, he was assured that it would all soon be drawn up into an Act of Parliament and the teenaged king “with sharp words and angry countenance” ordered him to carry on with the drafting. If the worst came to the worst, he would be granted a pardon. Montagu recorded that, as an “old man” – his own words (he was 65) – he “was in great fear as ever he was in all his life before, seeing the king so earnest and sharp”. So, he carried on.

But things did not go as planned. The king died on 6 July before a parliament could be called. His scheme for the succession, though approved by the Privy Council and most of the peers, was therefore still legally invalid. Northumberland nevertheless decided that it should be put into effect, and Jane was proclaimed queen on 10 July. The proclamation asserted that the crown had come to Jane by authority of the letters patent (as it called them) of 21 June. Yet within a fortnight the law prevailed and Mary’s title under the 1544 Act was accepted; it was Mary who was crowned. Northumberland was tried and executed for treason in August, Jane and her husband the following year. No pardons for the judges were forthcoming. The two chief justices, Cholmley and Montagu, must have felt some alarm when they were committed to the Tower. Was it a defence to treason that they were doing what the king ordered them to do? Probably not, in the case of a statutory treason. But after six weeks they were discharged with heavy fines of £1,000 (about £½M today). Despite their pleas in mitigation, Mary declined to reappoint either of them. The Solicitor-General (Gosnold) also lost office, though the Attorney-General and Sir John Baker somehow emerged unscathed, and Bromley J (another signatory, formerly of the Inner Temple) actually became Lord Chief Justice. Thus are the vagaries of public life.

So much for Edward’s ill-fated ‘devise’. And yet … Had he lived just a few months longer, to call a parliament in the Michaelmas term, our scrap of paper would have become law; Jane would have been assured of the crown; England would have escaped Mary I’s reign but missed the glories of Good Queen Bess. Assuming Jane or her sisters had male issue and established a House of Dudley, we would also have been deprived of the Stuarts, the United Kingdom, and the Hanoverians. Our nation’s history would have been completely different.

For the full video recording: innertemple.org.uk/librarytreasures

Professor Sir John Baker KC LLD FBA

Honorary Master of the Bench