Selden Society Lecture: The King’s Prerogative 1622; the Prime Minister’s Prerogative 2022

Continuing Constitutional Turbulence

The Seldon Society and Four Inns of Court Annual Legal History Lecture held on 1 November 2022

© Wikimedia Commons

When did the trouble start? It certainly did not help smooth things over in 1609 when King James I told parliament that “the state of monarchy is the supremest thing upon earth”, modestly adding that all the attributes of God agreed in the person of a King. That 1609 parliament included something like 100 lawyers from the four Inns of Court among its members, many rather troubled by the Scottish King’s approach, and it was unwise for him to prove his ignorance of the common law by claiming that “no law could be more favourable and advantageous for a King and extend further his prerogative”. It was even more unwise to fail to recognise the importance of the response, which in 1610 took the form of a Petition of Grievances. The Petition was a measured complaint against rule by proclamations, which tended “to alter some parts of the law”, and expressed concern that proclamations would “by degrees, grow up and increase to the strength and nature of laws”. What they perceived as the menace of ‘proclamations’ is now disguised by its modern manifestation, ‘statutory instruments’.

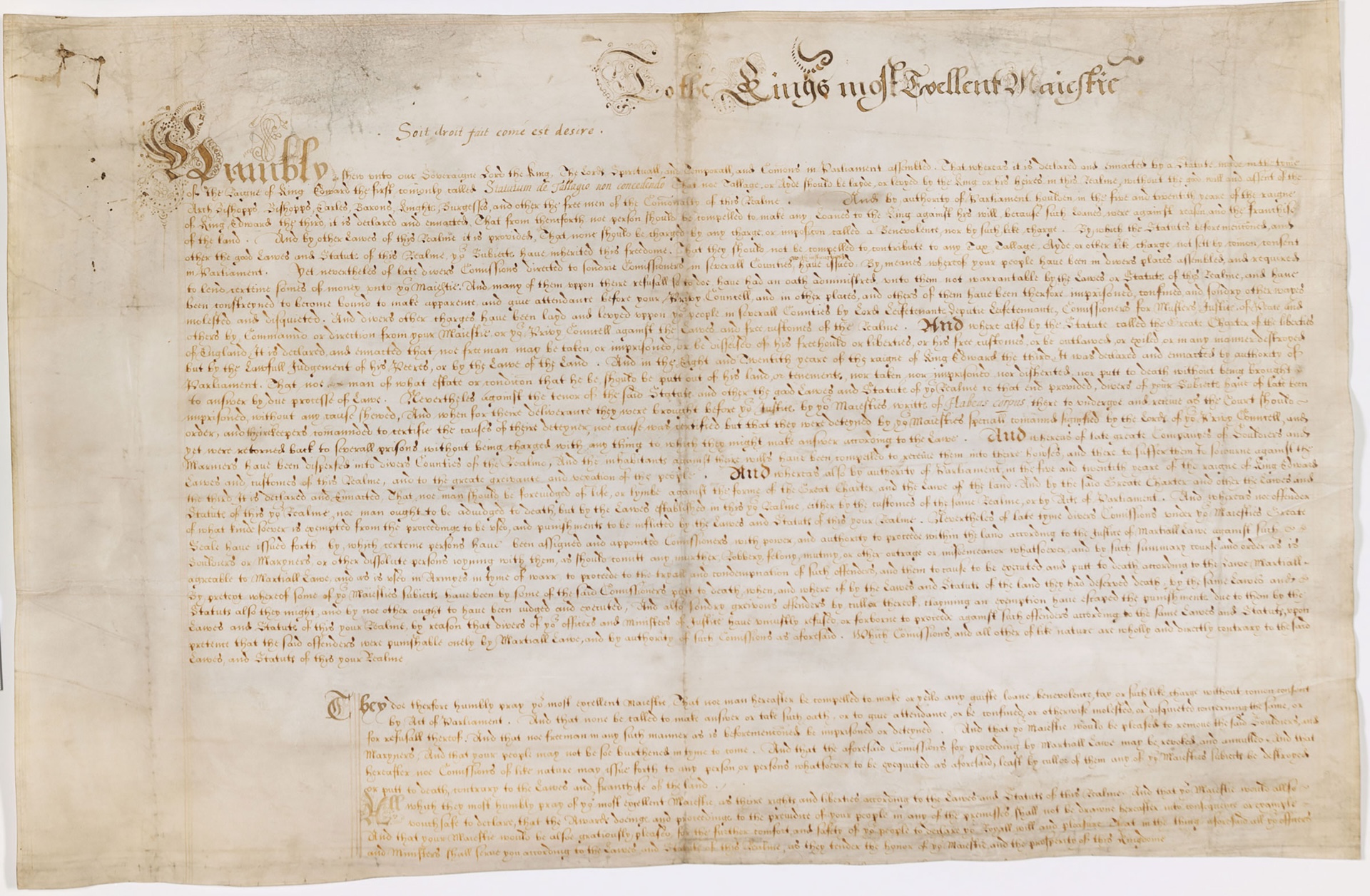

To the title of this lecture. By December 1621, the troublesome relationship between James I and the House of Commons boiled over. Again, they drew up a Declaration of Grievances. The King responded with outrage. The Commons offered a second petition reasserting their rights, respectfully inviting the King to take away “the doubts and scruples your Majesty’s late letter to our Speaker hath wrought upon us”. The King countered that their asserted rights were no more than whatever he was prepared to tolerate. So the Commons produced a Protestation. It was entered on the Journals. James I adjourned parliament. A few days later in the New Year he went to parliament. He demanded to see the Journals. He read the entry. He literally tore it out of the book “to be razed out of all memorials and utterly to be annihilated”. Parliament was dissolved because the Commons had taken “inordinate liberties with our high prerogative”. Sir Edward Coke, a former Chief Justice, was locked up in the Tower where he remained for seven months. Locking opponents up was an unpleasant Stuart habit: later our very own John Selden was deprived of his liberty more than once, and finally for five years.

We were now on the path, not an inevitable path, but the path which ultimately led to Civil War and execution of the King. Reflecting that awful chaos and turmoil, Thomas Hobbes produced The Leviathan, postulating concentrated power. “I authorise, and give up my right of governing myself to this man on condition that thou give up thy right to him and authorise all his actions in like manner… To the end he may use the strength and means of them all as he shall think expedient…” I was brought up to regard that philosophy of concentrated, effectively unconstrained political power with distaste, and still do. Passionately.

Within another 40 years, a new James I was driven out of his kingdom. That dramatic event required its philosophical justification, and in his Treatise of Civil Government John Locke provided it. Political society must establish legislative power, but the legislature violates its sacred trust if, among other things, it ignores the principle that it “neither must, nor can, transfer the power of making laws to anybody else…”

All was now well: we would never again be governed by the ‘King, in parliament’, the King tolerating parliament as he thought useful. Our constitutional settlement was the ‘King-in-Parliament’, two Houses and the monarch, the whole in a balanced equilibrium. Please recognise the vast difference between the King comma in Parliament, and the King hyphen in hyphen Parliament. The punctuation is critical.

Now, jump 400 years to 2022. The equilibrium of King-in-Parliament has become a mythical constitutional fiction. The Lords has negligible power, although still some influence. The head of state is a constitutional monarch, who notwithstanding his lifetime concerns has accepted ‘advice’ not to participate at COP 27. Constitutional power is vested virtually exclusively in the Commons, and although that is the principle, in reality the exercise of power resides in number 10 Downing Street, which nowadays exercises significant oversight over the Departments of State. Of course, modern Prime Ministers cannot lock up their opponents, nor do they remain in office for life. Despite those important distinctions I venture to suggest that true description of where actual power rests is the Prime Minister in the Commons. And at the end you can work out for yourselves where the punctuation, comma or hyphen, should be drawn.

For the purposes of this lecture, I chose 2022 because the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Act 2022 was expressly designed to restore the royal prerogative. The Prime Minister advises the monarch that parliament should be dissolved. I suggest that the monarch has no choice. In 1950, three situations were suggested where the monarch might take a different view to the Prime Minister. These were explained in a letter to The Times, written by the King’s Private Secretary, but signed with a nom de plume, “Senex”. That suggests, at the very least, concern that even his own very limited thesis would be politically controversial. I do not think it runs today. The monarch may, of course, advise the Prime Minister against a dissolution, but the exercise of the prerogative is in the Prime Minister’s hands. There is no other constraint. The Commons cannot reject its own dissolution. The jurisdiction of the courts is ousted. The monarch, whose prerogative the statute purports to restore, certainly cannot dissolve parliament, not even in our recent absurd circumstances. Only the Prime Minister, or the expiry of five years, can negative the results of the previous General Election. All those millions of votes binned, at the behest of one office holder. Indeed, we have reached the absurdity that while the Conservative party were electing Liz Truss, Boris Johnson remained Prime Minister and in law he, and he alone could have asked for a dissolution. The Commons, where the Prime Minister had a comfortable majority, rapidly, as it habitually does unless parliamentary time is becoming constrained, rejected a Lords’ amendment which would have tempered this modern manifestation of the prerogative, and required a majority, a bare majority, in the Commons to support its dissolution. Today’s Prime Minister can more or less echo King Charles I that “Parliaments are altogether in my power for their… dissolution”.

In the available time I want briefly to touch on two further important Stuart prerogatives which are now vested directly or indirectly in the Prime Minister. In passing, I highlight the penetrating foresight of Sir John Eliot who in 1625 identified the danger to what he thought of as the democratic process of leaving the control of business to one person: today that powerful weapon is in the hands of the governing party. Eliot too ended up in the Tower, where he died.

First, Elections. Charles I exercised the prerogative to control membership of the Commons. The simple device was to appoint those who were frustrating him in parliament as High Sheriffs of their counties. Such an appointment disqualified them from leaving their counties; so they could not go to London. These are names to conjure with, among them Coke, Phelips, Alford and Wentworth.

Second, the Honours system. James I created 600 knights within three months of his arrival. Francis Bacon described the title as “almost prostituted”. Nevertheless, he sought one for himself, expressing the hope that his own personal dubbing should not be “merely gregarious in a troop”. Much more important, as a precaution against the Lords supporting that hugely significant Petition of Right, in April/May 1628 Charles I packed the Lords, much smaller then than now, with six new Peers. I cannot discern any distinction in any of them except that one was a nephew by marriage of the King’s favourite, Buckingham, one was a favourite of the new Queen, and one bought a Viscountcy, no less, for a donation of £20,000, a vast sum to the cash-strapped King.

Two aspects of the prerogative, one already constantly misused by Prime Ministers from both sides: HOLAC, the Appointments Commission, apart from its own recommendations, cannot assess the suitability, or justification for appointment, but only the candidates’ probity. The House of Lords itself, which is desperate to diminish its size to sensible proportions has no voice. No one and nothing has any controlling influence over the Prime Minister. That prerogative still thrives 400 years on.

As to elections, the Elections Act 2022 has granted the party in power a significant measure of control over the Electoral Commission. Yet the primary requirement, indeed the very justification for this influential body in a modern democracy, is absolute political neutrality and independence of any political influence. Despite Lords’ amendments, again rapidly rejected by the Commons, that independent body must, not may, must now “have regard” to “guidance” from the Secretary of State. ‘Guidance’ is a newish phenomenon, legislation disguised by an emollient word. The result is a diminution in the independence of the Electoral Commission.

Leaving the Prime Minister directly appointing members to one House, influencing the elections to the other House, and solely responsible for dissolving parliament (not a bad hand), I must move beyond prerogative powers. Given the way musical chairs has been played recently with the identity of the resident at number 10 Downing Street it may seem a little audacious to focus on the Prime Minister in the Commons. But although Prime Ministers come and go, the office itself is untouched. We have become habituated, in John Locke’s penetrating phrase, to the transfer of lawmaking powers from the legislature to the executive. And worse, for the executive to approach its own responsibilities on the basis that a majority in the Commons enables it to do anything and everything. I make no comment about Trussonomics’, but those wide-ranging economic proposals were agreed by the Prime Minister and the Chancellor of the Exchequer and proclaimed to the nation before they were seen even by the Cabinet. Astonishing, but commonplace, policy proclamations that should be first made to parliament are now frequently made to the media first.

So back to where I began. Proclamations. There never was any constitutional objection to the King issuing proclamations which advertised existing law, or even which encouraged agreeable behaviour. There is none today. What the Commons asserted in 1610 was an “indubitable right” not to be subject to proclamations which enforced compliance with new law created by the Palace. They were following well understood constitutional principles. Today there are many rhetorical flourishes in the Lords about Henry VIII clauses in legislation, referring to the notorious Act of Proclamations 1539; but even that notorious Statute had its limitations and was repealed immediately on Henry’s death. That was no more than confirming the provision in the Act that it should not survive Henry’s death. Stephen Gardiner, who was there at the time, observed that nothing in the Act enabled anything to be done “contrary to an Act of Parliament or common law.” In 1555, the judges in Mary I’s reign asserted that “no proclamation by itself may make a law which was not law before, but they only confirm and ratify an old law and not change it”. I only mention that decision because Sir John Baker, the oracle of English legal history, draws attention to the observation in the report, so familiar to anyone who has practised at the Bar that although some contrary precedents were quoted, the justices “had no regard for them”. More important, in 1610 there already was a long-standing national antipathy to lawmaking by proclamations. The abolition of the Star Chamber in 1641, the enforcement authority, effectively ended the practice.

But our constitution evolves. The objectives of unacceptable Stuart proclamations are now achieved by delegated legislation. Now is not the time to address the way in which the emergency measures required by COVID-19 operated, but parliament was sidelined throughout. A declaration of emergency accompanied by the signature of a single minister on a statutory instrument, effectively locked us all down. There was no obligation to consult parliament for up to 28 sitting days, effectively six weeks. During the pandemic our lives were redrawn, and freedoms curtailed on the basis of over 500 statutory instruments. But we must not fool ourselves that this was either a new or a temporary phenomenon or confined to emergency situations. Largely, statutory instruments are not dealing with emergencies at all: new laws impinge on, adjust and govern our day to day lives like confetti falling at a wedding.

In 2022, our increased expectation of what central government and local authorities and quangos should provide, and indeed the myriad of societal issues which need regulation, has the consequence that secondary legislation is necessary, and often appropriate. In theory this is all under parliamentary control. First the powers are enacted by parliament. Second, there are, I think, 16 different ways in which parliamentary control over statutory instruments may be exercised. Well then, hurray, what am I fussing about? Just the reality. I venture to suggest that this reality would have been regarded by our ancestors in the 1620s as government by proclamation. Why?

The powers are gifted in ‘skeleton’ Acts: legislation which declares a policy but leaves implementation to statutory instruments. Take as a simple example, the recent Schools Bill. The Bill asserts that it is addressing the important question of ‘Academy Standards’. Yet there is not a word about standards. The legislation contains a list of controlling powers that by regulation may be exercised by the Secretary of State. Indeed, after about 18 powers, it confirms that they are merely ‘examples’ of what this Secretary of State may address. It will all be left to statutory instruments. It is a complete assumption of authority by the Executive. There is even a Henry VIII clause as early as clause 3, allowing amendment by secondary legislation even before the required academic standards themselves have been defined. Today when an Act of Parliament omits a Henry VIII clause it is only because someone in the Department has failed to press the relevant button on the computer. That is how commonplace delegated legislation has become, and how frequently primary legislation may be overruled by secondary legislation.

So, the second limb of parliamentary control. The constitutional theory that the exercise of any lawmaking powers granted by secondary legislation is subject to parliamentary control. In reality there is no such control. No draft statutory instrument can be amended. You cannot accept, say, 99 sensible provisions, but reject one obnoxious one. The executive controls business in the Commons, the danger identified by Eliot 400 years ago. For what the Whips perceive to be indiscipline, the penalty is service on the Commons Delegated Legislation Committees. The consideration given is minimal.

Since the 1980s, many thousands of statutory instruments prepared by government departments creating powers granted to ministers, including creation of criminal offences, punishable with imprisonment, have been laid before and accepted by the Commons. Just as for instance, between 2005 and 2009, over 6,000 statutory instruments were laid; in every single year between 11,000 and 13,000 pages of statutory instruments, over 50,000 pages of laws, came into force. In the session before COVID-19, 2017–2019, 2,323 statutory instruments were laid before the Commons. That is mind boggling. Even more shattering, since 1979, that is well over 40 years, the Commons has not rejected a single statutory instrument. 40+ years: not one among so many thousands. Since 1950, the Lords has rejected six, the last in 2015. This so shocked the Prime Minister that he set up an immediate review, the object of which was to curtail the power of the Lords over statutory instruments. As though the democratic process could be subverted by six occasions since 1950 when the Lords had, in effect, said no, not to primary legislation, but to the consequences of secondary legislation.

Since the 1980s, many thousands of statutory instruments prepared by government departments creating powers granted to ministers, including creation of criminal offences, punishable with imprisonment, have been laid before and accepted by the Commons.

That 2015 decision by the Lords is interesting. In 2006, the Labour-controlled Commons gave a minister power, by statutory instrument, to change benefits allowances. The intention was to increase them without reverting to parliament. They were then used by Conservative government, when Mr Osborne was Chancellor of the Exchequer, using the powers available to him in the statutory instrument to remove something over £4 million from the benefits system. The Lords rejected that proposal. The important moral is that once these powers have been given to the executive, they remain in place even when the electoral system has provided us with a different and new executive. These powers can be used, or misused, by any future government. They are not the prerogative; but the powers survive long after the government which created them, available to each succeeding government.

For years now concerns have been expressed by Committees of both Houses and many others. Not least Sir John Baker himself. Assurances are offered, but executives do not enthusiastically support reductions of their power. In November 2021, the Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee of the Lords published a report under this chilling headline Government by Diktat; A call to return power to Parliament. The title says it all, but it was intended “to issue a stark warning that the balance of power between parliament and government has for some time been shifting away from parliament… A critical moment has now been reached when that balance must be reset” At the same time the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee published its own report, equally chilling, entitled Democracy Denied? The urgent need to rebalance power between Parliament and the Executive. In summary it records “the abuse of delegated powers is in effect an abuse of Parliament and an abuse of democracy”. Members of these committees are hardly revolutionary: not a Guy Fawkes among them; to the contrary, their deep concern is the operation of our constitutional arrangements. Their membership is cross-party, including crossbenchers, and they are unanimous. Does the government of the day take any notice? No, they were ignored. If it had attended to them, the devastating criticism of the flawed constitutionality of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill – “as stark a transfer of power from Parliament to the Executive as we have seen…. The Bill is unprecedented in its cavalier treatment of Parliament” – would not have been made.

When it is concluded, study the Hansard Society Review of Delegated Legislation. For now, please study these reports from the Lords. They matter hugely. In their tone and in a widely different historical context, these reports represent today’s Petition of Grievances and the Protestation. Government by proclamation has returned, insidiously, in disguise. If it continues, apart from the requirement of a general election at least every five years (a provision which itself is open to extension by parliament) it will be Thomas Hobbes, not John Locke, who will have triumphed. For me that would be a constitutional catastrophe.

Rt Hon The Lord Igor Judge