Celebrating our Rare Books

By Inner Temple

The Library’s collections were reinstalled over a year ago, and it has been business as usual ever since … but all was not as it seemed. Behind the scenes, the Library team (and numerous patient researchers) quietly awaited the final piece of the puzzle – the return of the manuscripts and special collections. A treasured selection of the manuscripts was exhibited to accompany a talk by Master John Baker earlier in the year. Now, to celebrate their return, the Library and Archive team would like to focus the (low lumen) spotlight on some of the books from our special collections.

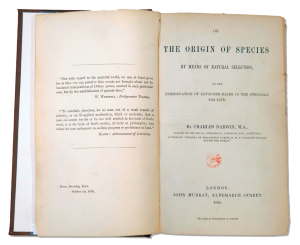

Widely regarded as one of the most important and influential scientific books ever written, On the Origin of Species was the first publication of Darwin’s theory of evolution to the general public, following the presentation of papers by Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace on the subject to the Linnean Society of London on 1 July 1858. Published on 24 November 1859, the first edition of 1,250 copies sold out immediately upon being offered for sale by the publishers. A second edition was published on 7 January 1860.

Simon Hindley

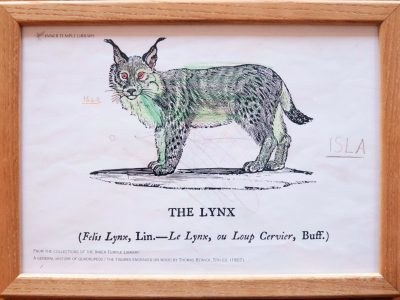

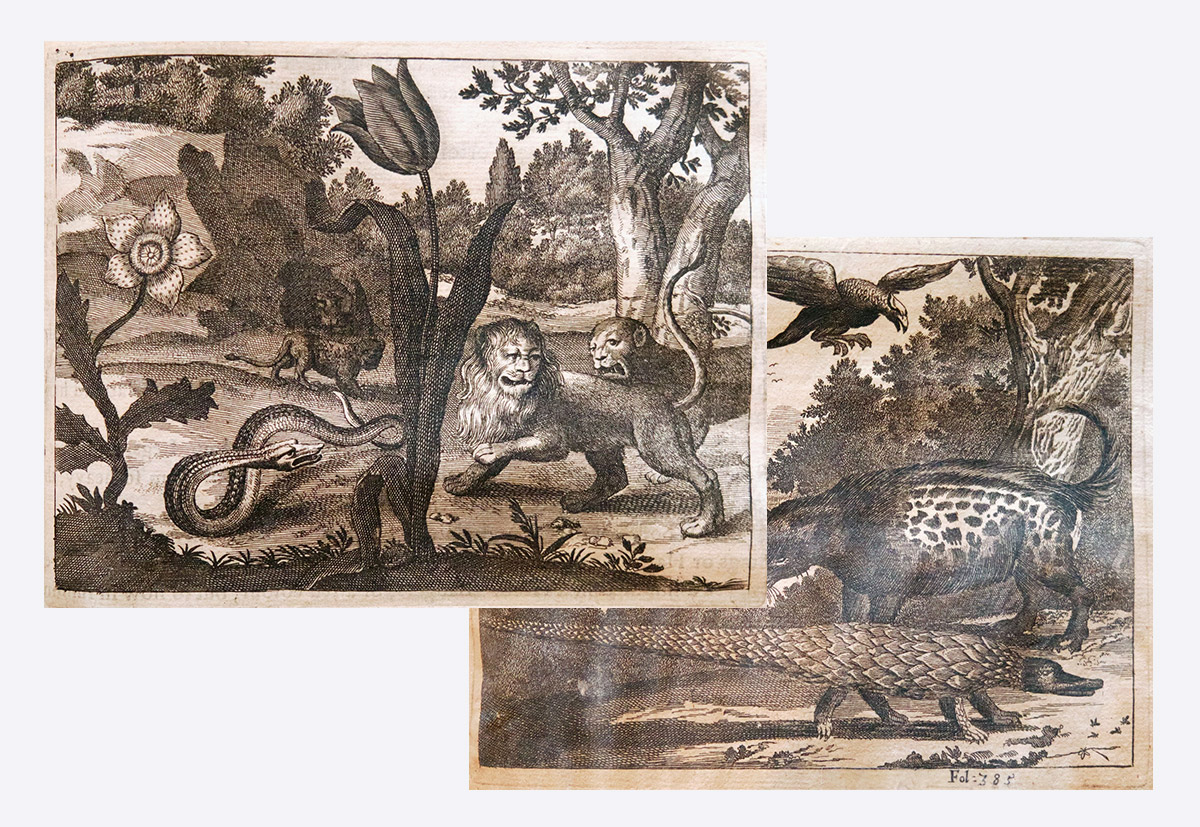

Until recently, I hadn’t seen Thomas Bewick’s super-cute woodcuts. It was only while preparing some colouring pages for our younger guests at the Temple Big Picnic that I really had the chance to truly appreciate them.

Thomas Bewick (1753–1828) was an English wood engraver and author known for his influential publications on natural history. We have a couple of titles in our collection, such as A General History of Quadrupeds and A History of British Birds (1805).

The birds are nice, but my true affections lie with the quadrupeds, which include some fantastical creatures such as the ‘Cameleopard’ (essentially a giraffe but a lot fancier) and a marvellously misshapen walrus (not pictured here, but I encourage you to enquire at the Library). It must be seen to be believed.

Sally McLaren

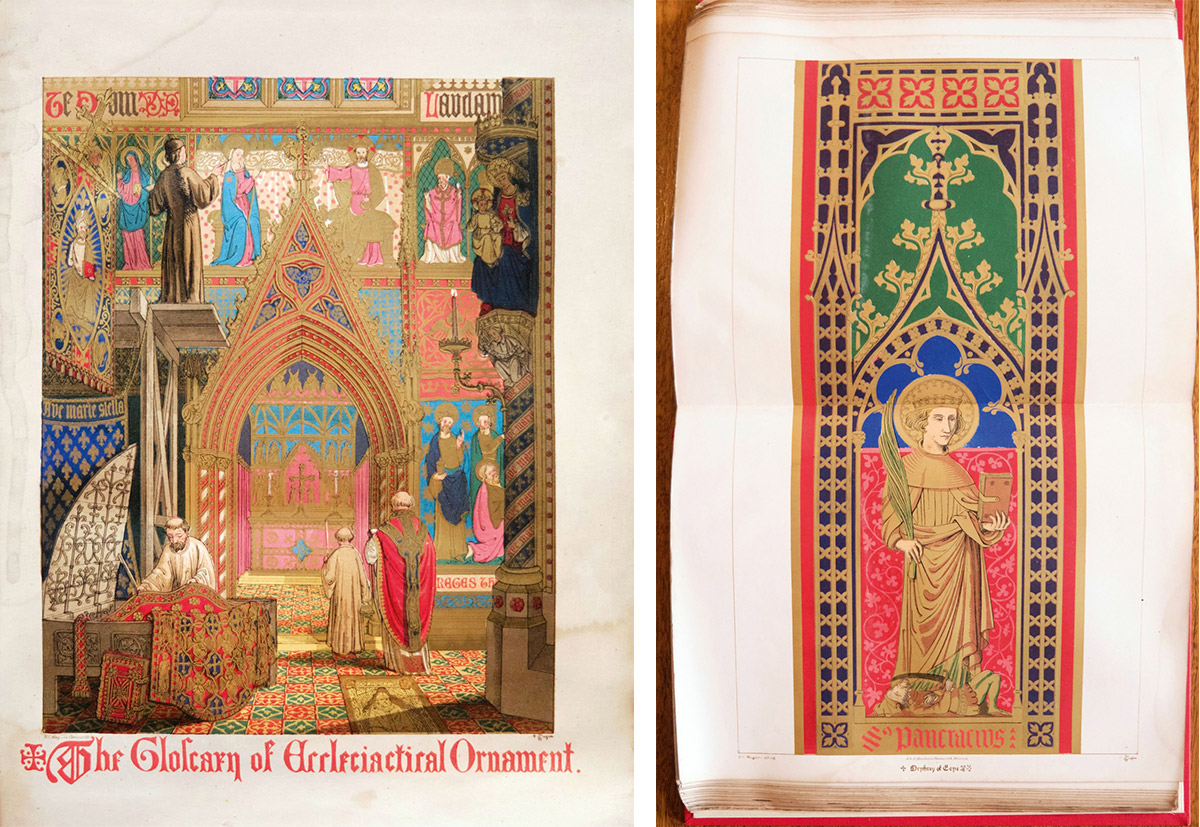

One of the Library’s non-law books of which I am very fond – indeed one of the few that I would like to own myself – is AWN Pugin’s Glossary of Ecclesiastical Ornament and Costume (1846). Firstly, it appeals to my taste for recondite knowledge. How many readers (then or now) would know what a Pax-Brede was? And how many could give the two (entirely different) meanings of the term ‘Ciborium’? Secondly, the highly coloured illustrations (chromolithographs: ‘state of the art’ technology at that date) are magnificent. Pugin’s text – over which he evidently took great pains, quoting from many historical sources – demonstrates in places that he was quite opinionated; here he is on the subject of ‘modern albes’ – an alb being a type of vestment: “[They] are for the most part strange departures from ecclesiastical antiquity. … In Ireland they are indescribably ridiculous … and very often made of uncanonical materials, to suit the caprice or whim of individuals.”

Michael Frost

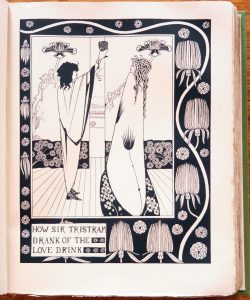

Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) was commissioned to illustrate this edition of Le Morte d’Arthur in 1893, when he was only 21 years old. This copy is from the second printing of 1909 (limited to 1,500 copies), after which the type was dispersed.

Having read and watched many adaptations of the Arthurian legends, I was excited to learn that we had a copy of Malory’s work in the Library. The book is filled with stories about King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin, and the Knights of the Round Table. These thrilling adventures sit alongside wonderful illustrations that capture the imagination and make the book as exciting as any modern film.

Tracey Dennis

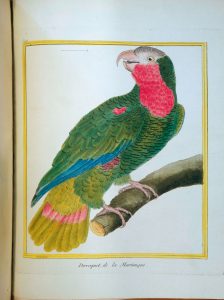

The French naturalist, Buffon (1707–1788), was the first to attempt a comprehensive work on natural history with his 44-volume Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particulière.

The copy in the Library’s collection, Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux, is in ten volumes (1770–1786) and forms a part of that work. The plates are hand coloured.

I have picked a colourful specimen of a parrot from Martinique. I have recently become fascinated with all birdlife, from watching robins, sparrows, magpies and pigeons in my garden, to travelling to wetland and coastal areas looking out for oystercatchers, curlews, turnstones, knots, lapwings and many more.

Tina Williams

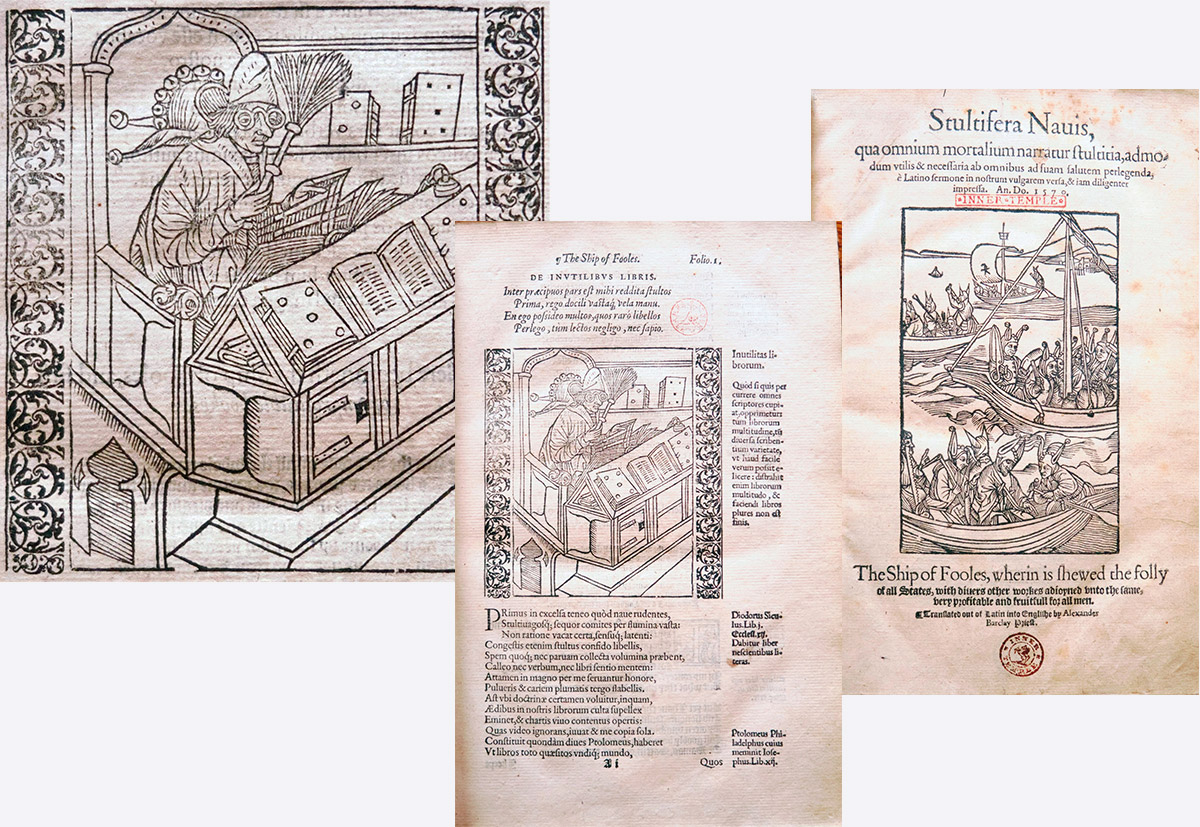

Arguably guilty of stockpiling books myself, I am fond of the fact the first ‘Foole’ is the ‘book fool’ who amasses books that he neither reads nor understands; in fact, he is “content on the fayre covering to looke”. Amusingly, the second berth on this ship of fools is reserved for “evill counsailers, judges and men of lawe” …

Of course, a librarian would not choose a book based on the pictures alone, but the woodcuts in Brandt’s Ship of Fooles are a delight.

Rob Hodgson

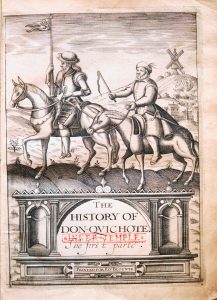

This first English translation of Part One of Cervantes’ Don Quixote was produced by Thomas Shelton (fl. 1598–1629) and was published in 1612. Unfortunately, only a few good copies, of which this is one, have survived.

This book reminds me of my first trip overseas by myself, when I travelled to and stayed on the coast of Andalucía with a trusty copy of Cervantes in hand. I do not quite recall if Don Quixote travels to Andalucía, but the large advertising boards featuring bulls, to be seen on many of the hilltops there, reminded me so much of the windmills he and Sancho Panza encounter on their journey. Memories of the book still burn vividly in my mind, entangled with my own travels in Spain.

James Rowles

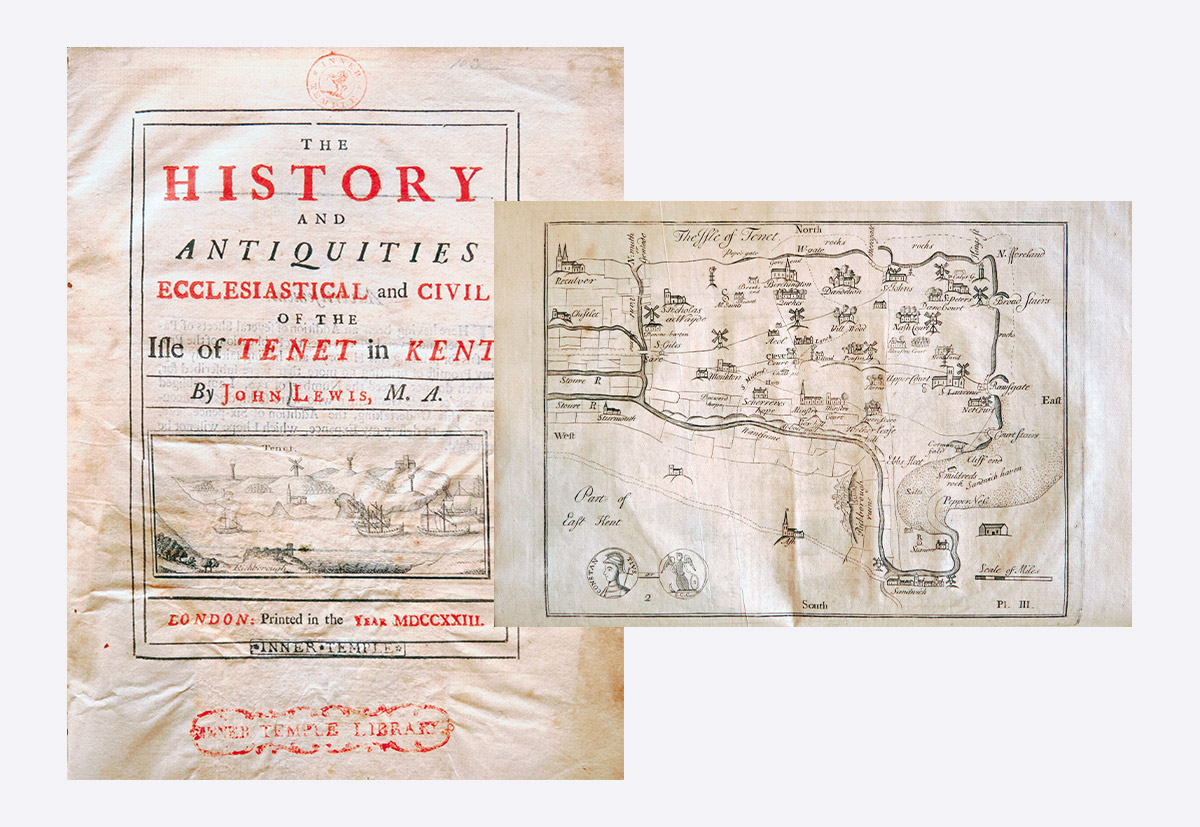

A particular favourite of mine, this book was written by the antiquary and clergyman John Lewis (1675–1747) and is the first of its kind to explore the richly diverse and ancient history of the Isle of Thanet in Kent, where I grew up. Although it is no longer an island, and is now a popular tourist and relocation destination, Lewis’s History and Antiquities proudly chronicles Thanet’s history as a major Bronze Age and Roman settlement right up to the early 18th century, delving into the area’s harbours, churches, and the everyday lives of its inhabitants. The Inner Temple Library is only one of around a dozen libraries in the UK to hold a copy of this first edition (which, excitingly, was also owned and donated to the Library in 1726 by Master Herbert Jacob, who lived near Thanet), and it is wonderful to have a book in our collections that is historically and personally important to me.

If you want to see more Tenet-related objects around The Inn, look out for the portrait of Gabriel Neve Esq. of Dane Ct. Thannet, Decr. 1743 hanging on the stairs by the second floor in the Treasury building just outside the Library.

Lily Rowe

John Ogilby (1600–1676), dancing master, theatre impresario, Irish Master of Revels, publisher, and the Royal Cosmographer to King Charles II (1630–85), created the first road atlas of England. The Library is lucky enough to possess his five Atlases, namely those for Japan, Africa, America, China and Asia. These Atlases were funded by lotteries and subscriptions to create ‘a series of Atlases to cover the world’. The first Atlas published was Africa, printed in London in 1670.

Ogilby relied on the anecdotes and explorations of others, having never visited any of the continents and countries depicted. His description of the religious nature of an elephant and its alleged expertise in ancient Greek is charming. The books are rich in illustrations, and Africa also contains the only contemporary biography of Ogilby.

The author lived and worked near The Inner Temple, where Tudor Street is now. He is buried at St Bride’s Church.

Celia Pilkington

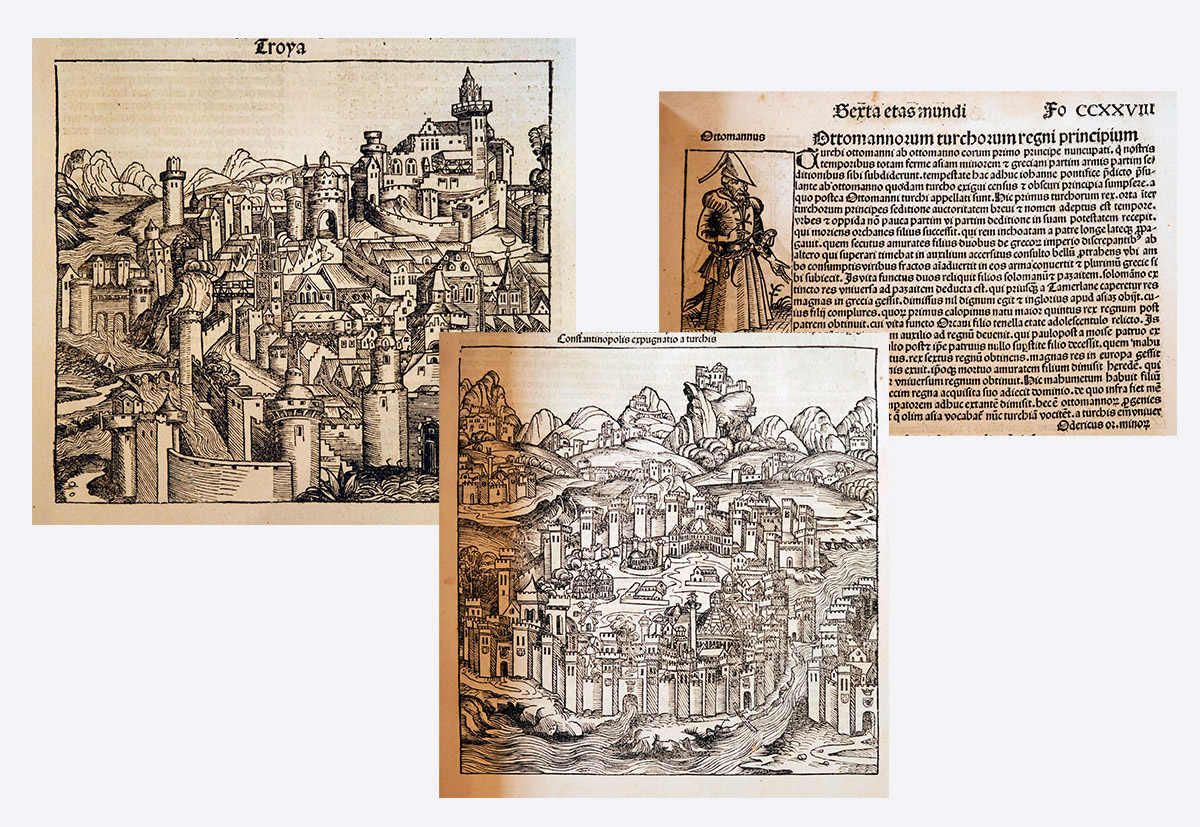

The Nuremberg Chronicle is an illustrated encyclopedia of world history, which was published and printed by Anton Koberger and authored by Hartmann Schedel, in Nuremberg in 1494. With a focus on Europe and the Near East, the book divides history into seven ages, including the future apocalypse, and uses biblical, classical, and medieval sources. The 1,809 woodcut illustrations are what The Nuremberg Chronicle is famous for. Designed by Michael Wohlgemut and his stepson Wilhelm Pleydenwurff (although the young Albrecht Dürer may also have contributed, as he worked for them a few years earlier), the combination of inaccurate sources and the lack of direct observation makes for the most entertaining illustrations, including the use of fantastical beings and European skylines for ancient and foreign cities.

Umut Kav