An Elizabethan Mystery

THE LEVER CANON LAW MANUSCRIPT AT INNER TEMPLE

This is a shortened version of a lecture he gave at the Temple Church, 28 February 2023. Thanks are due to Master Mark Hatcher; and to Rob Hodgson and Michael Frost of Inner Temple Library who displayed the manuscript there. Matthew McMurray and Andrew Gray at Durham University Library, and Professor Charlotte Smith at the National Archives. The lecture is an up-dated version of N. Doe, Rediscovering Anglican Priest-Jurists: V – Ralph Lever (c. 1530–1585), 25 Ecclesiastical Law Journal (2023) 66–80.

You might be familiar with modern mystery novels set in Tudor England – such as CJ Sansom’s series featuring Matthew Shardlake of Lincoln’s Inn; SJ Parris’ blockbusters with Giordano Bruno and Queen Elizabeth’s spy-ring; and then Edward Marston’s Nicholas Bracewell, theatre manager in Elizabethan London.

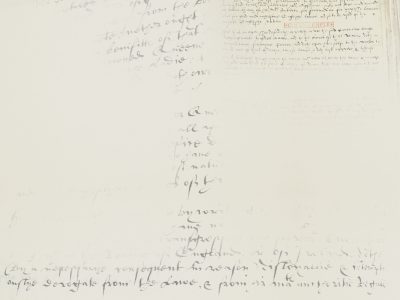

We have our own Elizabethan mystery at Inner Temple Library: a manuscript on the canon and ecclesiastical law of the Church of England, which regulated so much of people’s lives from baptism to burial, from marriage to wills. The title in the manuscript is: The assertions of Ralph Lever touching the canon law. Lever was born c. 1530 and died in 1585. These 55 years are crucial in the evolution of English ecclesiastical law. It was the hot topic. Under Henry VIII, parliament enacted statutes: to terminate the papal jurisdiction in England; to withdraw England from the European continental Church of Rome; to establish the Church of England as an independent national church; and to assert the royal supremacy in matters ecclesiastical. It was the Brexit of its day.

However – and Brexit legislation mirrored this – to fill the legal vacuum left by the demise of Rome, the Submission of the Clergy Act 1533 allowed the pre-existing Roman canon law to continue to apply to the new English Church (if not repugnant to the laws of the realm) and until reviewed by a royal commission.

No commission was appointed. Parliament provided for a review in 1535, 1543, and 1549; and by 1553, a commission had compiled a new code – the Reformatio Legum Ecclesiasticarum; but the project lapsed with the return of England to Rome under Mary I. The draft code was resurrected when the Church was re-established under Elizabeth I and published in 1571, but parliament rejected it.

The 1533 Act, revived on Elizabeth’s accession, also provided for the clergy Convocations of Canterbury and York to make law, with royal assent, in the form of canons. But it wasn’t until 1603/4 that Convocations made a new code of canons approved by James I – hardy things – they were not revised till the 1960s.

Also, in 1563, Convocation endorsed the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, and as the years unfolded parliament enacted many anti-Roman Catholic laws. The new Elizabethan church settlement was summed up famously by Richard Hooker (Master of the Temple in the 1580s) in his Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity.

These landmarks provide the legal setting for our Inner Temple manuscript. Ralph Lever was born in Lancashire, the fifth of seven sons. After Eton, like three of his brothers, he entered St John’s College, Cambridge: BA 1548 and, after becoming a fellow 1549, MA in 1551. A Protestant reformer, he was exiled under Mary. On return, he resumed his fellowship and later married.

Lever had wide interests. In 1563, he wrote a book about a board game “for the honest recreation of students and other sober persons in passing the tediousness of time to the release of their labours and exercise of their wits”. He wrote another in 1573 – The Art of Reason, Rightly Termed Witcraft: “a perfect way to argue and dispute” on Aristotelian lines; it is one of the earliest books on logic in English.

He wrote another in 1573 – The Art of Reason, Rightly Termed Witcraft: “a perfect way to argue and dispute” on Aristotelian lines; it is one of the earliest books on logic in English.

A colleague at St John’s (its master) was James Pilkington, also a Lancastrian, a reformer in exile, and Bishop of Durham from 1561. He appointed Lever as his chaplain, Rector of Washington, Archdeacon of Northumberland, and Prebend at Durham Cathedral. In 1572, Lever challenged the latter’s episcopal visitation articles, was summoned to court, but resigned as archdeacon to avoid censure.

A commissary on Pilkington’s death, in 1577 Lever is at loggerheads with the dean and chapter over leases. He resigns his offices to be Master of Sherburn Hospital. Founded by the Bishop of Durham 1181 for leper monks, and rebuilt as alms-houses, Lever secured an Act of Parliament 1585 to: incorporate the hospital; allow the bishop to make rules for it and appoint its master; and oblige the master to nominate the brethren who took an oath to obey the bishop’s rules.

In 1583, Lever also sought reform of the cathedral statutes at Durham that, according to him, were “defective in sundry points touching religion and government”. But the dean and chapter were hostile, and Lever died in 1585 before his new scheme was considered. He was buried in the cathedral.

Alongside trying to reform Durham cathedral statutes, and securing the Act of Parliament for Sherburn Hospital, it would not be surprising if Lever turned his attention to the national ecclesiastical law. Hence the tract, full title: The assertions of Ralph Lever touching the canon law, the English papists and the ecclesiastical officers of this realm, with his most humble petition to her majesty for redress. The Inner Temple text is among its Petyt manuscripts bequeathed to the Inn in 1707 by William Petyt, Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London, Treasurer here 1701–02, and buried at the Temple Church. But the collection gives no date for the tract, though the dates of neighbouring manuscripts in the volume – also on church affairs – range from 1573 to 1580. The text is not signed by Lever, so we assume it is a copy, copyist unknown.

Questions arise about the date and authorship of the tract. Conway Davies’ catalogue of Inner Temple manuscripts (published 1972) lists the tract but is silent as to date. Davies (a Welsh historian from Llanelli) made notes on the Petyt manuscripts, now among his papers at the National Library of Wales. The notes to the Lever tract are the same as those published in his 1972 catalogue – except that he has ‘nd’, presumably for ‘no date’, which does not appear in his published catalogue. The Bodleian Library did a full search of all their online and published catalogues, but this has not traced any reference to a manuscript matching Lever’s; Cambridge University Library did the same – again, no trace.

Beyond these catalogues, scholars have dealt a little with the tract as part of their wider studies, but they differ on its date, authorship, and classification.

First, John Strype (d. 1737), in his Annals of the Reformation in England (1725), dates it to 1562, and presents it among “Papers prepared” for the Convocation of 1563. He describes Lever as “a learned canonist” who wrote the tract to regulate the canonists, canon law, the abuse of excommunication, and “the unjust dealings” of some judges. But Strype did not find Lever at that Convocation, “or that it came before the synod”, though he presents it as being “agreeable to the matters…relating…to a reformation of things amiss in the church, and very probably offered in this juncture”. Strype then gives the title and text without further comment. Lambeth Palace Library has no record that the tract is among their collections relating to the Convocation of 1563.

Second, is the great modern historian of the canons of the Church of England, Gerald Bray. On the basis of the Petyt manuscript at The Inner Temple, in 1998 Bray dated the tract to 1563, though Bray refers in a footnote to the tract as it appears in Strype (who dates it 1562). Bray does not mention Conway Davies.

Bray places the tract firmly in the reformers’ camp. He says, it was not written by a “canonical fundamentalist” for whom canon law had the same status as doctrine. The reformers protested against such a view and Bray writes: “No-one put it more clearly than the anonymous canonist whose assertions have come down to us as the work of Ralph Lever”. Yet, Bray then says the tract is “attributed to Ralph Lever, though it seems virtually certain he did not write it”.

Crucially, Bray gives no reason for this claim, though he describes Lever as “a convinced protestant…unhappy with the pro-Genevan tendencies of a number of the returned Marian exiles”. Like Strype, Bray links the tract to the 1563 Convocation which had “a clear desire for a reform of the ecclesiastical laws along what would later be called ‘puritan’ lines”. However, later Bray also states: “Nor is it known when it was composed, though it must have been in or shortly after 1563”. Bray then gives a brief overview of themes in the tract.

Third, another date, another classification. In 2008, David Marcombe dated the tract to 12 January 1585, citing The York Book at Durham University Library. Indeed, Marcombe had argued in his 1973 doctorate, on the history of the Dean and Chapter of Durham Cathedral, that Strype had “incorrectly” dated it to 1562. For Marcombe the year 1585 makes sense because the 1580s coincide with Lever’s proposals for legal reform at Sherburn Hospital and Durham Cathedral.

The York Book is now in Durham Cathedral Archive. In it is a manuscript of Lever’s petition with the same heading as that at The Inner Temple. The heading is followed by the date 12 January 1584, not 1585. But this date is inserted by a different and later hand to that in the manuscript itself. However, unlike The Inner Temple’s “Ralph Lever” appears at the end of the Durham manuscript in the same hand as that of the manuscript itself, not in the hand of the date, as if it were signed by Lever. But the manuscript is a copy, so it is not his signature.

From Durham to London: The National Archives. The State Papers show that Lever petitioned the Privy Council once in 1577 (the Durham dispute over leases), twice in 1582, once in 1583, and a fourth of uncertain date (all to resolve a dispute with the Bishop of Durham), and in 1585, on the bill for Sherburn Hospital. There is no sign of our petition. Charlotte Smith at the National Archives sums up: “no definitive answer but, based on the patterns of correspondence, 1562/3 looks too early; but circa 1585 would make sense”.

Back to Marcombe. He thinks Lever was the author; and had “sometimes radical Protestant beliefs”; engaged in “chronic contentiousness”; and “approved of continental Protestantism”. But he believed the English Church sacramentally and doctrinally authentic; and thought the Calvinist church polity in Geneva and other reformed churches was “not so fit for our state as our own”. Also, Lever was “a staunch opponent of Catholicism” and “of the continued use of canon law”, considering those who “upheld the canon law [as] Papists and traitors”.

However, Lever and his work are rather less puritan-reformist than these scholars portray. Our manuscript has 21 paragraphs, each contains numerous assertions. Once more, it deals with canon law; English Roman Catholics; and church officers. There are small differences in wording between our manuscript and that at Durham; and the Durham manuscript has two more paragraphs, ie, 23 in all.

Most of his assertions are orthodox, they simply articulate the ecclesiastical law of Elizabethan England in statutes, canons, and so on; but he does not expressly cite any of them. Also, while Strype and Bray style Lever a “canonist”, he was not trained in canon law: the faculties of canon law at Oxford and Cambridge were dissolved under Henry VIII. Nor was he a civil lawyer; he neither trained in civil law at university nor practised law in the church courts. Though as Archdeacon of Northumberland he presided as judge in his archdeacon’s court.

First, the canon law. By this, Lever means the Roman canon law. On the one hand, he criticises it: “The canon law… made by the church of Rome is in exceeding many points contrary to the written Word of God and repugnant to the positive laws of this realm”. It “does chiefly… establish the bishop of Rome his usurped… authority over all Christendom”. And it “breeds…superstition and a certain security that there is no further increase of faith required, but to believe as the church of Rome believes – it is rightly termed ‘the pope’s laws’”. But Lever gives no specific examples of how these offend scripture or English law.

On the other hand, Lever accepts that some papal canon law is rooted in the Bible and natural law, and it applies in England as part of the law of the realm. A more nuanced stance than Marcombe’s. Lever writes: “the rules, ordinances and decrees…in the books of the canon law and yet have warrant by the Holy Scriptures and by the laws of nature, and thereupon are in force here at this day, being established by act of parliament to this end, that justice may be ministered to all her majesty’s subjects, ought not to be named, reputed or taken by [those] subjects for foreign or popish laws, but for good and wholesome English laws”.

In this assertion, Lever’s ‘act of parliament’ is the Submission of the Clergy Act 1533, revived by Elizabeth in 1559. The passage is hugely significant, it is one of the first recorded Elizabethan statements that papal law continued to apply in England on the basis of that statute – a view common among later ecclesiastical lawyers, alongside the idea that papal law applied here before and after the 1533 Act on the basis of its reception in England, as held in Caudrey’s Case (1591).

Lever is not as radical as other reformers, like William Stoughton (d 1612), a civil lawyer favouring a presbyterian system of church polity: “the papal and foreign canon law is already taken away and ought not to be used in England”. Lever is more like Richard Cosin, Dean of Arches in the 1580s, who defended the English Church against presbyterianism and, like Hooker, cited many works by continental Roman jurists as well as medieval papal law.

Second, Lever on Roman Catholics. He writes, anyone who “believes the church of Rome…to be the true church of God,” and that it “does not err…in making of canons, laws and decrees, and in commanding the same to be…kept of all Christian nations, is a papist” and “not to be taken…as a subject in the church and commonwealth of England”. Likewise, anyone who professes “to be a loyal subject to Queen Elizabeth, and yet believes…the Church of England…is not…to be taken for, the true church of God” is no “member” of that Church.

Lever then defines the Church of England as “reformed by the written Word of God and established by public authority”; in it the sacraments are “rightly administered”, the gospel “truly preached” and liturgy “duly set forth according” to scripture. This all echoes the 39 Articles and Hooker – not the Calvinists.

Lever then defines the Church of England as “reformed by the written Word of God and established by public authority”; in it the sacraments are “rightly administered”, the gospel “truly preached” and liturgy “duly set forth according” to scripture.

Third, ecclesiastical officers. At the outset, he asserts the rule of law: church officers’ decisions must be authorised by law; but Lever (like Hooker) has a pluralistic view of law. In decision-making “the officer ought to assure himself to have warrant by the written Word of God, by the law of nature, by the law of nations, and by the positive laws of this realm”. Failure to do so derogates “from the law” and from the “legal authority” of the Crown, and in turn offends God.

As a result, all “officers and magistrates ought daily to meditate upon Holy Scripture and by it be directed in all their public affairs” and when “they…make laws”. Why? “For then does God stand in the congregation of princes and is judge among them when he directs them by his Holy Spirit and…holy word”.

Lever also opposes discretionary power under the law, “The commonwealth…is best governed that has most of her causes determined by law and fewest matters left to the judgment of her officers and governors”. Lever presages Dicey here.

Fourth, positive laws made by humans – they must pertain to matters on which scripture is indifferent; they must not conflict with scripture; the subject must obey them; positive laws may be changed only by lawful authority; and, as to legal reform, he says, a frequent and “needless change of law is most perilous”.

The Durham manuscript here has an extra paragraph: “The equity of human laws is not impeached by the corruption of the judge”, echoing the 39 Articles: receiving the sacraments is not affected by the unworthiness of the minister.

Lever ends his discussion of positive law with an assertion about the purpose of all laws; it is highly theocratic: “The end of all laws, both divine and human, and the chiefest care that all princes, magistrates and lawgivers ought to have is this, to see the people of God to be taught, to give Caesar that is due to Caesar, and to God that is due to God”. These ideas too represent basic Anglicanism.

Fifth, he criticises, “bishops, their chancellors and other ecclesiastical officers” for excommunicating people “contrary to the written Word of God” and “such rules in the canon law…at this day in force by the positive laws of this realm”. Rather, the censure may be imposed only with “sufficient cause”; if “fault” is established; and by a “proceeding in law”. Or else, it is “contrary to all divine and human laws”, and “the conscience” of those censured “is free afore God”.

Excommunication was often the subject of reform at this time. The Canterbury Convocation in 1563, passed articles about delays attendant on it; in 1580, it heard an argument “concerning [its] reforming”; and in 1584, it passed a canon for the “reforming” of “some abuses in excommunication”. Obviously, the years involved in these reforms do not particularly help us in dating the Lever tract.

Sixth, the Court of Delegates, since 1533, the final appeal court in spiritual matters. Lever’s criticisms are: there was no appeal against a Delegates’ decision; its judges “misuse the sacred chair of justice”; and they do so without the “the fear of God”, the trust the Queen “did repose in them”, and “to great annoyance” of many. Some contemporaries of Lever also criticised the court, because, for instance, its judges did not usually give reasons for their decisions. But Lever is not as radical as Calvinists like Stoughton who sought its abolition.

Finally, Lever’s petition: “For redress of all inconveniences and mischiefs which hereupon have happened…since the last parliament…your most humble suppliant makes petition to your most excellent majesty that such order be taken by this parliament assembled as does best agree to your majesty’s laws already established” etc. The petition seeks better administration of the law rather than reform of law itself. The Durham version of the petition is longer than this.

Excommunication was often the subject of reform at this time. The Canterbury Convocation in 1563, passed articles about delays attendant on it.

Petitions to parliament from this period, in its archives, were destroyed in the fire of 1834. Nor is our petition in parliament’s journals. So, for the date of 1562 or 1563 (Strype, Bray), the ‘last’ parliament was in 1559, which passed statutes on Lever’s topics, including those reviving the 1533 Act on Roman canon law and the Delegates Court, the Act of Supremacy, and the Treason Act. Also, as Lever notes, since that parliament there had been problems with its laws. “This parliament”, then, could that of 1563 summoned, as its record says, to uphold religion “notwithstanding that at the last parliament a law was made for good order to be observed in the same but yet…not executed” and to make new “plain, few, and brief” laws (also in Lever). Again, the parliament of 1563 addressed Lever’s topics: royal supremacy; treason; and excommunication.

Alternatively, if the Lever tract is from 1584/5, as Marcombe claims, then the relevant parliaments would be those of 1580 (the last parliament) and 1584 (this parliament). The 1580 parliament passed statutes requiring obedience to the crown, on recusancy, and on sedition. These subjects, too, continued to be problematic. The 1584 parliament considered a bill to ‘overthrow’ the church courts and it enacted statutes on the safety of the monarch, Jesuits, and pardons.

In short, the parliamentary agenda and legislation for 1563 and 1584 both contain subjects addressed by Lever and so seem not to help us to date his tract.

To sum up our Elizabethan mystery, Lever was a Protestant reformer, but entangled himself in the establishment, using it to reform his cathedral and hospital. The tract in The Inner Temple manuscript is difficult to date: 1562/3 or 1584/5.

Assuming Lever wrote it, his work on ecclesiastical law is mostly that of a classical Elizabethan Anglican; there is more in it of Hooker than Travers. He criticises the administration of the law rather than the law itself. Above all, it is significant because it is one of the earliest statements of the continuing applicability of Roman canon law in England under parliamentary statute.

What Shardlake, Bruno, and Bracewell would have thought of Lever and the tract, I know not. What is certain is this: the Lever manuscript is just one of scores of such items in the ecclesiastical collections at The Inner Temple library; to-date these items have not been studied as we have studied the Lever text here; and identifying and exploring these items, at the Inn, will enhance greatly our understanding of the turbulent history of the interplay between law and religion.

For the full video recording: https://youtube.com/live/3SBQDz4ll9U

Norman Doe LLD

Academic Bencher

Professor of Law, Cardiff University

Chancellor of the Diocese of Bangor

This is a shortened version of a lecture he gave at the Temple Church, 28 February 2023. Thanks are due to Master Mark Hatcher; and to Rob Hodgson and Michael Frost of Inner Temple Library who displayed the manuscript there.

Matthew McMurray and Andrew Gray at Durham University Library, and Professor Charlotte Smith at the National Archives. The lecture is an up-dated version of N. Doe, Rediscovering Anglican Priest-Jurists: V – Ralph Lever (c. 1530–1585), 25 Ecclesiastical Law Journal (2023) 66–80