A History of the Inn through its Treasures

This article is an edited text of a History Society lecture given on 22 February 2023

It is a great pleasure to talk to you tonight about some of the Inn’s treasures and the part they have played in the history of The Inner Temple.

The plate (the name for collective silver and not silver plate) of The Inner Temple consists of both religious and secular items. The religious silver and silver gilt regalia used in the Temple Church is jointly owned by the Inner and Middle Temples, both Inns have their own collections of secular plate which is used for dining and display purposes, much like other City Institutions and Oxford and Cambridge Colleges.

The Inner Temple collection is wide ranging and many of the important pieces can be seen in the Hall display showcases or being offered for view on dining tables for dinners. This evening we are considering plate that helps to explain the historical association and development of the Inn, combined with royal association and the Temple Church. Generally, the items chosen are chronologically presented and one of the items has such royal importance it has been included because it links other matters.

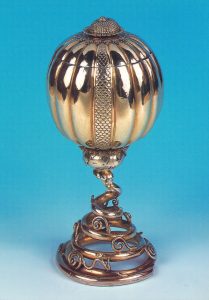

The earliest piece of hollowware in the collection is the silver gilt melon cup, London hallmarked for 1563–4. There is some debate whether this cup has been in the hands of The Inner Temple at this time or acquired at a later date. On 1 May 1563 there is mention of a communion cup to be made for the church being co-funded by the Inner and Middle Temples, more about this later. Further, 4 days later on the 5 May 1563 it is again minuted as: ‘Order that Mr Warner’s money and 20li for the cup be recouped out of the debt owed by the society to Mr Fuller, late Treasurer….’ 20 li at the time would have been around £7,000 in today’s money and the question is would this have been enough money to make the melon cup? I believe it would, to make a similar cup today would cost around £7k to £10k using modern production techniques. I also believe a contemporary communion cup could have been made for considerably less than £20 at the time.

The first mention of the melon cup would appear to have been included in the inventory of 1703–4, with the entry

‘1. Gilt cup with cover’ – could this cup have possibly survived the Civil War in Inner Temple ownership when so much silver was lost? We just don’t know.

Some regard this as being a poppy-shaped cup, why would you wish to drink from a poppy when you can drink from a sweet melon? The cup to me represents a Cantaloupe melon, you will see the twisting stems shown in the spiralling base of the cup, also the shape of the cup body very much conforms to the fruit body. This variety of cantaloupe melon arrived in England in the mid-16th century and is mentioned in Hill’s ‘Art Garden’ of 1563. (He published under the unusual pseudonym of Mountain Didymus).

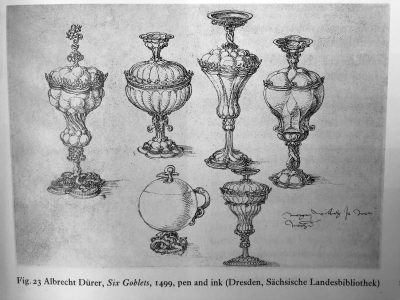

Further the cup bears the maker’s mark of Henry Watson, who employed European journeymen one of whom was Maurice van Myden. He would probably have brought his paten book with him illustrating similar sketches to those by Albrecht Durer of 1499. Van Myden might have made the cup to a very novel design at the time, but as a foreign worker would not have been allowed to register a maker’s mark at Goldsmiths Hall.

The final words might be left to the colloquial expression to cut the melon, to decide a question, illustrated by the exposed segment in the cup’s body showing the internal seeds, eminently suitable for the Inn.

Apparently made by the Royal Goldsmith John Williams the passage records: “To the King’s goldsmith for half the cup which is to be provided to His Majesty £333 6s 8d.”

A subsequent entry for the next year states: “To the goldsmith for making a cup of gold which was given to the King with a velvet case, the one half £7 3s.”

The other half would have been paid by the Middle Temple.

My sketch of the cup described as a steeple cup, and this gold cup would have been a very large object. It is recorded that the cup weighed 200 and a half oz of gold. A large silver steeple cup of the period could stand 24 inches and weigh 60 oz, or so. Gold is twice as dense as silver so this cup would have been a third larger than a silver cup (100 silver oz equivalent), possibly 36 inches high.

The cup was given to James I in 1608 as a New Year’s gift and he is reported to have considered it one of his richest jewels, with the corresponding return of the Letters Patent. On the instructions of Charles I, it would appear that the gold cup was sent to Holland, possibly in 1629 with much other treasure, or it was accompanied by the rest of the Crown Jewels and further royal treasure with the Queen and the Princess Royal in 1642, when they travelled to Holland to help secure a loan for the royalist cause in the Civil War. The Crown Jewels returned later to be eventually destroyed by Cromwell but it seems not the Temple cup. Still, it looks like a particularly good deal to have secured the Temple lands in this way.

In today’s money the £666 would equate to £330,000 for the cup’s manufacture. If we take the price of gold today, 200.5 oz will cost approximately £300,000; and if we say the cost to make the cup is £30,000, not so much has changed here in over 400 years, but the price of the Temple estate is certainly worth a great deal more.

A pair of silver gilt chalices being part of the plate belonging to the Temple Church. Each of the chalices are engraved with Latin inscriptions, one translated as being: “George Croke Armiger (bearer of arms, in fact he was knight) Treasurer of the Inner Temple and Nicholas Ouerburye Treasurer of the Middle Temple Anno Domini 1610”.

The other has a similar inscription but to the Middle Temple.

The general account book Vol II p 53 records: “1609 To Terry a goldsmith for two new communion cups for the Temple Church abating of exchange of one (possibly the communion cup of 1563 that I mentioned before), 13 li 12s 2d the Middle Temple paid one half 6li 16s 1d.”

If one cup cost £6 16s 1d in 1609 it seems most unlikely that the cup of 1563, at a cost of £20, was other than the melon cup.

Who was Terry? My view is that the pair of chalices were supplied by the shop-keeping goldsmith in Cheapside, John Terry hence the Terry in The Inner Temple records. The chalices, however, bear the maker’s mark of a monogram mark FT which was not a mark for Terry but for the actual working goldsmith who made the chalices, probably Thomas Francis.

It is remarkable that these silver gilt treasures belonging to the church survived the melting pot at the time of the Civil War; apparently, they were secured in a locked steel box in the church, so that they can still be used over 400 years after they were made. The altar cross and candlesticks used at that time in the Temple Church were less fortunate.

A silver layette basket purchased by the eminent criminal barrister Sir Edward Marshall Hall, from Tessiers Ltd, my old family firm, on 19 June 1925, was presented by five Benchers to Inn. By any standards this is an exceptional silver object, made in Holland in the Hague by Hans Coenraet Brechtel between November 1644 and November 1645. These baskets, usually made of wicker, were a customary gift to a pregnant woman in the later stages of her confinement.

The pierced and repoussé base is decorated with grapes, vines, birds, animals and a dominant central coat-of-arms with lion and unicorn supporters. The arms depicted here are of William II of Orange (1626–1650) and his wife Mary (1631–1660), eldest daughter of Charles I. Mary was born on 4 November 1631 and married William in London on 2 May 1641 at the age of 9. According to the marriage treaty, Mary was to remain in England until she had reached her twelfth year; her husband was to allow her £1,500 a year as pocket money. Turmoil in England caused Mary to be taken by her mother to Holland, somewhat earlier than expected, in 1642, probably with Temple gold cup. William, himself only fifteen at the time of the marriage, tried to sleep with his eleven-year-old bride in June 1643. This is noted in a diary called Gloria Parendi kept by William’s cousin, William Frederick, in contravention of his parent’s wishes, and was stopped just in time apparently by a lady-in-waiting. A second small marriage ceremony took place in The Hague in November 1643, on Mary’s twelfth birthday.

The pierced and repoussé base is decorated with grapes, vines, birds, animals and a dominant central coat-of-arms with lion and unicorn supporters.

It was not until 1644 that Mary was installed in her full conjugal position and was able to give audiences, receive foreign ambassadors and fulfil all the functions of the State. This she did with a gravity and decorum that was remarkable for her years. She was also celebrated for her grace, beauty and intelligence, but her ‘general education’ was described as defective, and she found difficulty in writing.

It is not possible to say precisely when William and Mary consummated their marriage; even in the summer of 1644 William had hardly any contact with his wife, treated her badly and had many lovers, amongst them the two daughters of Field Marshal Van Brederode. It is possible that the basket contained a message to apologise and encourage there to be a satisfactory union with the two young people.

If we consider in a brief form the two sides of the basket, his side on the left and hers on the right, in his lower quarter the weasel represents his unwelcome approach across from her collared squirrel, the virgin, the owl sits on the side of his lion’s head suggesting that he has wisely seen the light, the error of his ways, the crow talking through a wreath at the very top, represents an allegory of hope for victory. Whatever the message, the basket appears to have worked. Mary is reported to have had a miscarriage on 12 October 1647, and was definitely pregnant when her husband died of smallpox on 6 November 1650. She is reported to have rushed through the palace wailing and threw herself on his dead body only to be pulled away by concerned courtiers.

The horn was blown before dinner at eleven and supper at six to call people to Hall, a practice that has now ceased but is remembered by some Benchers. Records from early times mention horns being purchased similar to the two shown here in 1621, 1630, and 1673. The Inn now has two silver capped horns. One, with silver mounts, was made by Thomas Phipps and Edward Robinson II in London in the 1780’s and engraved 1786; the other, larger, also with silver mounts is hallmarked London 1936–7 by an unknown maker WT and was given by Sir Frank MacKinnon.

Inner Temple horn calling had stopped in 1870 and Sir Frank campaigned to restore the practice in 1936. Because the head porter made such a poor sound with the 1780’s horn he commissioned another with a reeded mouthpiece to help the blower. You may be interested to know that the horn blower was entitled to a pint of beer after a performance.

An inspection of the early volumes of the Calendar of Inner Temple Records gives many indications of the equipment needed for dining. There are mentions of the purchase and repair of silver spoons, ewers and bowls, also, supplies of food and linen. One of the records suggests that silver finger bowls, silver ewers and rose water basons were a necessary part of every well-kept cupboard of plate.

Up to the end of the 17th century, dining was a pretty messy business, the fork was only gradually introduced to Britain, from Italy, during the end of that century. The main eating utensil used before then was a knife for meat and a spoon for gravy, combined with the hand.

On the high table, the hands would have been washed at the beginning of the meal, sometimes before grace and at the end of the meal before the table was left. Those below the salt would wash their hands on entry and on leaving the Hall using side bowls. The Inn’s present head silverman, William Gallagher, tells me that the tradition of the youngest server tasting the water to ensure it was not poisoned has not happened in his time.

On Thursday 5 August 1661, Sir Heneage Finch, Solicitor-General, being Reader of the Inn, gave his feast in the ancient hall. To this feast the King was bidden, arriving in the royal barge from Whitehall accompanied by the Duke of York, the Lord Chancellor, various ministers of state, and a great number of the nobility. Perhaps the ewer and basin used at this occasion was not quite important enough for the next royal visit in 1671. Sir Heneage, now Treasurer, wanted something a little grander. The King and the Duke again honoured the Treasurer with their presence on Candlemas Day, 2 February, on which occasion the Hall was again arranged for their reception, and a performance of The Committee, a comedy by Sir Robert Howard, was given for their entertainment by the players of the King’s House.

The large silver ewer and basin were made by Thomas Minshall in London and is hallmarked for 1670–1671. The basin has a diameter of 24” and weighs 119 oz. An interesting note, one of Minchall’s apprentices, John Clarke did not continue his career as a goldsmith, instead he became Keeper of the Lions at the Tower of London, which was the first menagerie in London. This was reported as being a more dangerous occupation compared to goldsmithing, the lions were known to maim or kill their keepers.

If this large ewer and basin were placed before the King at each end of the meal, with the generously engraved coat-of-arms surrounded by the elegant feathering plumage popular at the time, carved on the plain reflective silver surface, it would have been a most noticeable display of the Inn’s heraldry, status and wealth at the culmination of the feast and the royal visit.

The Pegasus salts might also have been found on the table. The Inner Temple Pegasus is first mentioned in records of the Christmas Revels of 1561. Robert Dudley helped resolve a land dispute between the Inner and Middle Temples; at the time he was the Queen Elizabeth I’s favourite, and it has been suggested, because he was also Master of the Queen’s Horse, that the choice of a Pegasus reflected his association with the Inn.

The Pegasus salts might also have been found on the table. The Inner Temple Pegasus is first mentioned in records of the Christmas Revels of 1561.

One of the most noticeable manifestations of the Pegasus is the realistically chased table saltcellars. Each of the 16 silver models are formed as a winged horse in flight supported at the front with a strut that forms part of the scrolling base. A removable shell salt dish is positioned between the wings. Made in the mid-19th century and all bearing London assay marks, one for 1849–50, eleven for 1850–51 and four for 1882–83, they were formed by the eminent silversmiths of the age, the Fox brothers, George and Charles. The family name was associated with silver manufacturing from circa 1801 in Old Street, in the City of London and then until 1921 in Soho, in the West End. It had not always been plain sailing for the silversmithing company and in the early years a petition for bankruptcy was made against the Fox family business, but the firm eventually flourished in Old Street until 1852, before moving to Soho. They made work for many of the leading London jewellers including my old firm, Tessiers Ltd in Bond Street, but principally for Lambert & Co of Coventry Street. The quality of their work was confirmed by the inclusion of articles made by them in the Great Exhibition of 1851.

We now move to modern times. Any dinner needs light, and the eminent silversmith Anthony Elson has given the Hall just that. He designed and made four candelabra for the millennium in 1999, four candelabra for the celebration of the 400 year’s charter granted by James I in 2008 and four candlesticks as a gift from Master John Deby in 2011.

The millennium candelabra each have stems formed as four supporting columns, symbolic of the Purbeck marble columns in the Temple Church, surmounted with interlocking Romanesque arches rising from a trumpet-shaped circular base, the four light branches of reverse ‘c’ scrolls with castellated drip pans, issuing from a central Pegasus standing upon a symbolic calyx of the conjunction of the planets Saturn and Jupiter; such a conjunction occurred on 28 May 2000. Before the 17th century, this event was widely supposed to herald apocalyptic changes. The most recent great conjunction occurred on 21 December 2020, Brexit occurred in January of that year.

The similar 400th anniversary of the Charter celebratory candelabra are made to a slightly smaller form, and they have a calyx of interlocking thistles and the candlesticks each have two demi-Pegasus rising from the bases. The general height of these lights makes for a more relaxed meal and enables cross table conversation.

There could be much more to add this evening, but time moves on. I hope you have enjoyed this talk whether your interest is historical, about silver or you just wished to see the new extensions to the Treasury Building.

For the full video recording: innertemple.org.uk/treasures

Richard Parsons

Silversmith and Jeweller